Tajikistan: A tale of remittances dependent economy in times of COVID-19

Posted on : May 25, 2021Author : Arpita Giri

The global scenario of the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic indicates that the migrants and the migration-based economies have been deeply affected by the current crisis. In this context, the present article will look at the issues and challenges being faced by Tajik migrant workers and their impact on Tajikistan due to disruption in the remittances.

The pandemic has made a widespread impact on the workforce globally. Among them, migrant workers have been disproportionately affected. A large number of migrants enter Russia every year and among them, Central Asians have the highest number. According to Russian Border Service, around 3.8 million citizens of post-Soviet states entered Russia in 2019, out of which 875,000 were from Tajikistan.[1] The actual numbers are much higher as many of the migrant workers enter Russia using the irregular route.

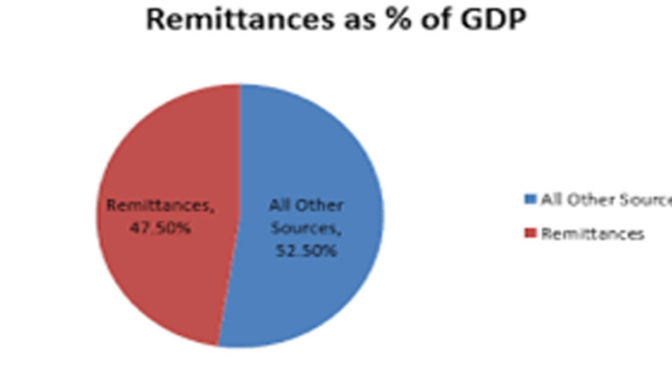

Tajikistan is a small, landlocked and mountainous country. More than half of its population is involved in agriculture. Remittances accounted for nearly half of the country’s GDP in 2013.[2] In 2018, the remittances from Tajik workers abroad was $2.2 billion which is equivalent to 30 per cent of GDP, making it rank among the top five countries which received the highest remittances as a share of GDP.[3] Remittances have continuously been an important contributor to the reduction of poverty in the country. In some of the poorest region of the country, remittances help families afford food, healthcare, education and other basic needs. In some households, especially Female-Headed Households (FHHs), money earned by the migrant member remains the only source of income.

Following the outbreak of COVID-19 in Russia in March 2020, due to the adoption of social distancing and lockdown measures, many migrant workers have found themselves in precarious condition. They have lost jobs across various sectors – housing, service and construction sites – due to the closure of economic activities. A survey conducted among Central Asian migrant workers in April and May of 2020, immediately after the outbreak of the pandemic, found that 75% of surveyed migrants had been either laid off or forced into unpaid leave, and over 50% had lost all sources of income. They mostly relied on social network for survival.[4] In Russia, a significant number of Central Asian migrants work in exploitative conditions, which is characterized by poor and irregular payments. They often live in overcrowded and unhygienic conditions with inadequate access to sanitation. The illegal status of many of these workers makes them an easy target for a bribe by corrupt officers. These vulnerabilities increase the risk of infection from COVID-19.

The closure of the border and suspension of all means of transportation further compounded the situation. It was reported that many workers were found stranded along various border points requesting authorities to let them go to their home country.[5] The pandemic has also affected the scope of migration for millions of Tajiks who were contemplating joining the Russian labour force. Both Tajikistan and Russia are still struggling to contain the spread of the virus and Russia is reluctant to open its borders, thus the future looks bleak for the Tajik migrant workers.

There has been a dramatic drop in remittances coming to Tajikistan following the outbreak of the pandemic. As early as April 2020, World Bank reported that the Central Asian region is experiencing an economic contraction not seen even during the worst economic crisis in the region.[6] Many households in Tajikistan are suddenly confronted with severe difficulties in meeting their basic needs like food, health and housing expenses. The problem of unemployment also spiked in the country due to the closure of domestic economic activities and the inability of many in the workforce from migrating to Russia. This is a matter of concern for the country which is already struggling with the growing number of COVID-19 cases and increased pressure on the health care system. To avert the crisis, Tajik Government has sought financial assistance from International Monetary Fund (IMF).[7]

The country was already paying a huge social cost for the large scale migration. Most migrants from Tajikistan are men. Thus, being a traditional society, the migrant status of men exposes women to multiple vulnerabilities. Irregular flow of remittances and abandonment of wives by their migrant husbands are the major concerns for women. Also, due to the continued absence of men, the responsibilities of women increases manifold. In rural areas, the role of women in agriculture has increased significantly increasing the female share of the agricultural labour force from 59 per cent in 1999 to 75 per cent by 2019.[8] Due to the absence of men, polygamy has become common in Tajikistan. The divorce rate has doubled between 2005 and 2010.[9] A study conducted in the Khatlon region shows that in four out of ten divorces recorded in Khatlon in 2014, one partner mostly the husband was a labour migrant.[10] In many cases, wives are left behind to manage the households and later husbands divorce or abandon them and remarry. They also stop sending money home so women are left alone to take care of children.[11]

Along with this, there is a rise of the shadow economy which comprises transnational criminal organizations and groups who exploit the desperation of people to migrate. This is in the form of illegal, irregular migration and human trafficking. These organizations were earlier in the drug trade and are now dealing in trafficking. Trafficking is considered more lucrative than drug trade as supply is abundant with huge markets to exploit and humans as a commodity can be traded multiple times.

The issues and vulnerabilities of migrants and governance of migration have always been an area of concern. In recent times, Tajikistan has acknowledged migration in its various national plans and policies. The country is also a signatory of various International and Regional conventions on the protection of rights of migrant workers. However, lack of democracy in the country and limited participation of civil society organizations are major hindrances in the policy formulation. Lack of official statistics on migration, reintegration of returnee migrants, diversification of migrant destinations are the key areas, the country needs to work on.

Migration has for long been seen as a solution to the ills that plague Tajikistan. The remittances from migrants and the investments made by them in the country improve living standards encourages economic development and creates employment. Remittances, however, are not sufficient to improve the status of all migrant households and is mostly utilised to meet daily consumption. Moreover, remittance dependency leaves the country vulnerable to external shock. Earlier also, following the Russia/Ukraine crisis in 2014, there was a huge drop in remittance flow to Tajikistan impacting its GDP.

References

———-

[1] Kanatbekova, A. and Gulina, O. (2020), “The Economics of Migration: Russian Experience”, Legal Dialogue, 24 June 2020, [Online: web], Accessed: 1 May 2021, URL: https://legal-dialogue.org/the-economics-of-migration-russian-experience. [2] Trilling, David (2014), “Tajikistan: Migrant Remittances Now Exceed Half of GDP”, Eurasianet, 15 April 2014, [Online: web], Accessed: 1 May 2021, URL: https://eurasianet.org/tajikistan-migrant-remittances-now-exceed-half-of-gdp. [3] Lemon, Edward (2019), “Dependent on Remittances, Tajikistan’s Long-Term Prospects for Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction Remain Dim”, Migration Information Source (MPI), 14 November 2019, [Online: web], Accessed: 1 May 2021, URL: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/dependent-remittances-tajikistan-prospects-dim-economic-growth. [4] Burunciuc, L. and Izvorski, I. (2020), “Central Asia: The First Economic Contraction in a Quarter Century”, World Bank Blogs, 8 October 2020, [Online: web], Accessed: 1 May 2021, URL: https://blogs.worldbank.org/europeandcentralasia/central-asia-first-economic-contraction-quarter-century. [5] Trilling (2014). [6] Burunciuc and Izvorski (2020). [7] Eurasianet (2020), “Tajikistan: Coronavirus brings bonanza of aid, but zero accountability”, Eurasianet, 29 July 2020, [Online: web], Accessed: 1 May 2021, URL: https://eurasianet.org/tajikistan-coronavirus-brings-bonanza-of-aid-but-zero-accountability. [8] Lemon (2019). [9] Putz, Catherine (2018), “The Feminized Farm: Labor Migration and Women’s Roles in Tajikistan’s Rural Communities”, The Diplomat, 4 January 2018, [Online: web], Accessed: 1 May 2021, URL: https://thediplomat.com/2018/01/the-feminized-farm-labor-migration-and-womens-roles-in-tajikistans-rural-communities. [10] Dodarkhujaev, R. (2015), “Tajik Labour Migration Boosts Divorce Rates”, Institute for War & Peace Reporting (IWPR), 27 January 2015, [Online: web], Accessed: 1 May 2021, URL: https://iwpr.net/global-voices/tajik-labour-migration-boosts-divorce-rates. [11] ibid

Arpita Giri

Adjunct, Asia in Global Affairs