The RCEP trade agreement: The road less travelled?

Posted on : June 7, 2021Author : AGA Admin

On November 15, 2020, 15 countries – members of the Association of Asian Nations (ASEAN hereafter) and 5 regional partners – signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP hereafter), arguably the largest Free Trade Agreement (FTA hereafter) in history. The RCEP will cover about a third of the world’s population, and potentially could add $209 billion annually to the world incomes, and $500 billion to world trade by 2030. Its key distinction to most other trade deals of comparable size is the fact that it is, in the majority, driven not just by key emerging market economies but also by economies that are beginning to exert a much more influence on global supply and value chains in recent times, such as Bangladesh and Vietnam. As understood by the figure, the RCEP member states have accounted for a growing proportion of global trade and are set to become the world’s largest trading bloc in existence today. As a conglomerate dominated by emerging economies, their share is only set to grow further in the coming days.

The RCEP’s Growing Role in Global Trade (Source: Brookings)

The RCEP incentivises supply chain harmonisation across the region but also caters to the political sensibilities of the stakeholders, giving them a greater footing and bargaining power in the new global economic order. The RCEP is more than just a conglomerate of emerging market economies (EMEs hereafter) engaged in freer trade without any barriers, expanding into cross-border investment flows among some of the fastest-growing economies of the world. The new global economic order is witnessing a re-alignment in trade and supply chain mechanisms with major emerging economies, taking the centre stage. India is a member of the ASEAN and ASEAN+ and several other significant bilateral and multilateral trade agreements. These existing trade relations should have seen a logical and natural progression through India’s membership of the RCEP which would have also allowed India to gain a relatively greater foothold in many of these supply chains and investment flows which are set to become even more deglobalized and regionalised now in the aftermath of the COVID pandemic.

India and Trade liberalisation

Trade theory has consistently been a strong proponent of free trade of goods and services, labour and capital. However, a growing wave of protectionism and trade has dominated global trade recently. Over the last two decades a rich academic literature examining the removal of trade barriers in developing countries like India, Brazil etc have emerged, enabled due to widespread trade reform across the developing world. This research has shown that trade liberalisation increases aggregate domestic productivity and welfare by reallocating market share from the least to the most productive firms, with the former, exiting the market, and the latter, expanding their businesses. While it is difficult to assess whether the trade war will lead to a significant shift in the global trade paradigm, in the current scenario, India should carefully review existing FTAs before signing new ones. India’s decision to exit the mega trade deal was taken after negotiating the new deal for over 7 years in the backdrop of several unresolved issues concerning market access, existing FTAs, non-tariff barriers faced by Indian exporters, services trade, rules of origin, among others. Evidence from recent FTAs suggests unfavourable gains to India’s trade partners. Working of India’s trade balances with FTA.

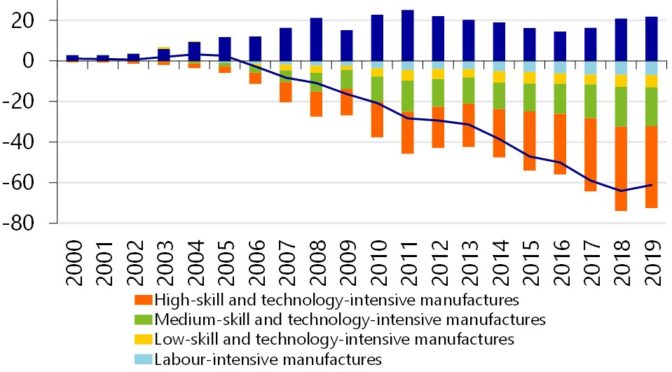

India’s Bilateral Trade Deficits and FTAs (Source: NITI Aayog)

partner countries merits attention. While India was often tagged as the ‘troublemaker’ in the deal negotiations, Indian policymakers stood their ground when it comes to the interest of the domestic producers, especially regarding Chinese exports of subsidized goods to India. The India – ASEAN FTA, India’s biggest trade deal witnessed a deficit that rose from $5 billion in 2011 to $22 billion in 2019. In the same period, the India – Japan FTA saw the deficit increase from$4 billion to $8 billion and the agreement with South Korea from $8 billion to $12 billion.

As the Niti Ayog paper, ‘A Note on Free Trade Agreement and their costs’ points out, India’s exports to FTA have not outperformed overall export growth or exports to the rest of the world. Only about 22 % of exports are to FTA partner countries. FTAs have not entirely served the purpose. On the contrary, nearly 30-35% of all imports are from FTA partners, with a corresponding cost in terms of revenue impact being about Rs 65,000 crores for FY-20. India’s engagement with trade partners has been growing over the years but the benefits and gains have been largely asymmetrical. Apart from economic factors, India’s decision to not join the RCEP had a strategic dimension, given China’s domination in the engagement and India’s long standoff with Chinese troops in Ladakh.

The Chinese Conundrum

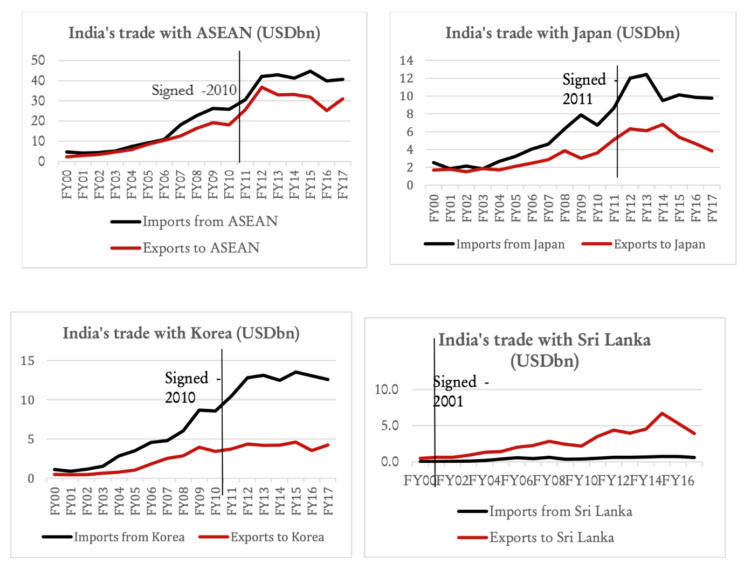

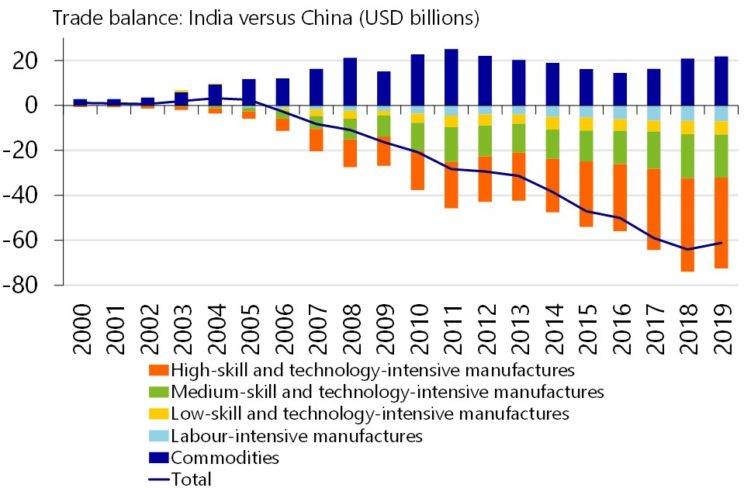

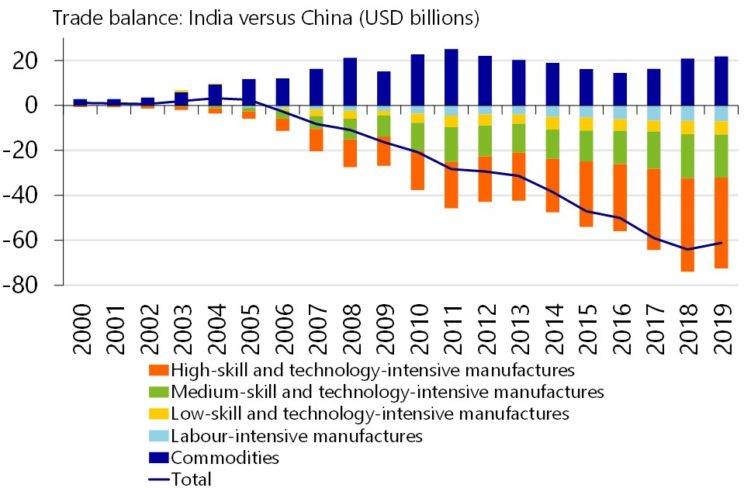

India’s widening trade deficit with China (Source: NITI Aayog and CEIC)

Text book trade theory teaches us about the benefits of trade liberalisation, particularly of unilateral cutting of tariffs that make an economy competitive in the long run. However, although the size of the economic pie increases with trade, reform is particularly hard because the winners from trade liberalisation are usually dispersed while the losers remain concentrated, and thus their voices, more vociferous in opposition. The entry of China with economies of scale in many sectors, enabling it to expand its export base and thereby, destroying the domestic manufacturing capacity in many emerging economies in the last two decades, has led to further isolationism across the world. The RCEP is seen to be China-centric and is expected to elevate its economic and political influence in the region. It is an attempt to further consolidate its position as the leader across the region, garnering tremendous political and economic capital. India has an unfavourable trade deficit with China while China’s share in India’s imports is a huge 14%. India’s export to China is at a meagre 5% of its export to the rest of the world. The disproportionate trade balance is further amplified by the composition of exports and imports. India’s export to China mainly consists of primary products like minerals, ores agro-chemicals whereas imports from China mainly consist of high-value items like capital and manufactured goods like machinery and engineering goods. One of India’s principal concerns has been that any FTA of this nature would lead to a flooding of its domestic markets with imports from other trade partners (particularly China), thereby weeding out similar and competing for domestic alternatives which might be relatively more inferior or uncompetitive, leading to extremely skewed outcomes. The fear of domestic markets being flooded with Chinese products is not just based on anti-China dispositions but also on a much larger and fundamental fear of Indian products not being able to compete with their foreign counterparts.

India’s widening trade deficit with China (Source: NITI Aayog and CEIC)

Despite periods of high growth, India’s share in global merchandise exports has stagnated to around 1.7% which partially alludes to a concern about the competitiveness of Indian exports in the global market. Lack of adequate credit, prohibitive interest rates, lack of firm-friendly legal and policy frameworks have become huge constraints to mobilise trade. Another significant structural impediment to ensuring better market access is the logistical costs of running a business. India’s world ranking in World Banking Logistics Preparedness Index has only worsened throughout the years, indicating either a performance gap in trade facilitation or no improvement in these barriers. In India, the cost of logistics as a percentage of GDP stands at 14 % while that of the USA and Germany at 8.5% and 9% respectively.

The Lure of Protectionism

India has been infamous for its extremely restrictive set of non-tariff barriers on trading partners which further hamper the quantum of trade. With the current pandemic, the Modi government’s push ‘Atmanirbharta’ push only implies a greater decoupling from global trade and supply chains. While this sort of a protectionist approach might seem attractive to core nationalist voters, it makes little sense for an emerging economy like India which has massive untapped potential in terms of taking greater reigns in global trade. One of the massive drawbacks of these protectionist measures is the lack of any concerted effort in any consensus-building around structural changes to streamline the reform process. The major stakeholders are not part of the discussions and this creates a disconnect between agents and the state. The political economy behind India’s already slow reform process presents major challenges to a structured and logical trade policy in the country. Successive governments over the years have adopted a hap-hazard approach in dealing with issues that are at the heart of India’s trade policy.

India’s inability to get its membership in the RCEP over the line, along with inabilities to further trade deals with major economies such as the US and the EU, also suggests the presence of common roadblocks which we must take very seriously, going forward.

- Choosing strategic partners for free trade: The US and Europe have been India’s trade partners. Given the huge trade complementaries between India and these countries, they are bound to be natural allies for trade. The US and Europe’s share in India’s exports have increased from 38% to 43% even though they don’t have any FTAs with these economies. Focus must be on deep bilateral trade deals instead of multilateral ones should be India’s goal for the time being.

- Getting India’s House in Order: India’s share of the manufacturing sector has stagnated around 17% in overall GDP. The manufacturing sector is critical to economic development in a vast and populous country like India as the multiplier effect leads to two to three additional jobs created in other sectors for every job created in the sector.

Phasing out import duty protection gradually: Safeguarding domestic interests is imperative in the post-COVID world. However, AtmaNirbhar Bharat does not mean resorting to protectionism as good quality imports are inevitable in sectors where domestic capability is lacking. Indian industry needs to be made aware that unlimited protection will do more harm than good; gradual phasing out import tariffs from time to time, especially with strategic trade partners, should be the norm as critical sectors grow with government hand-holding over time.

The RCEP would have been a greater opportunity for India to consolidate its position as an emerging economy and leverage a greater footing in multilateral institutions, with the prospect of having significant improvements in the country’s internal trade linkages as well as adapting with the competing economies through modern supply chains and trade networks. As an instrument of foreign economic policy, trade has virtually become a non-existent tool in India’s strategic approach over the past decade, underscored by flatlining exports for a majority of this phase. The inability to ink key trade deals and carry them over the finishing line would also be a source of concern for any onlooker interested in Indian trade policy.

RCEP is over for India, but free and fair trade is not.

Works Cited:

- Prachi Priya and Aniruddha Ghosh,” India’s Out of RCEP: What’s Next for the Country and Free Trade? “, The Diplomat, December 15, 2020

https://thediplomat.com/2020/12/indias-out-of-rcep-whats-next-for-the-country-and-free-trade/2. Hugo Erken and Michael Every,” Why India is wise not to join RCEP “, Raboresearch – Economic Research, December 29, 2020

https://economics.rabobank.com/publications/2020/december/why-india-is-wise-not-to-join-rcep/3. Ila Patnaik and Radhika Pandey, “RCEP would’ve led to flood of imports into India. Reform is a better way to boost exports”, The Print, November 20, 2020

https://theprint.in/ilanomics/rcep-wouldve-led-to-flood-of-imports-into-india-reform-is-a-better-way-to-boost-exports/548051/4. Sharan Banerjee, “Mirror, Mirror on the Wall…RCEP is the biggest of them all”, December 8, 2020

https://sharanbanerjee.substack.com/p/mirror-mirror-on-the-wall-rcep-isYash Vira

Intern, Asia in Global Affairs

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the text belong solely to the author, and do not in any way reflect the point of view of Asia in Global Affairs.

Excellent article Yash. Absolutely correct observation about RCEP – “The entry of China with economies of scale in many sectors, enabling it to expand its export base and thereby, destroying the domestic manufacturing capacity in many emerging economies in the last two decades, has led to further isolationism across the world. The RCEP is seen to be China-centric and is expected to elevate its economic and political influence in the region. “ They have destroyed a lot of smaller countries by flooding the markets with Chinese imports, thus crippling the economy. Even US & UK have been flooded with Chinese imports that has led to many local manufacturers going out of business! Excellent article, Yash!