The Great Maritime Game

Posted on : June 10, 2018Author : AGA Admin

A rather prosaic definition of the Indo-Pacific notes “ ……sometimes known as the Indo-West Pacific, it is a bio-geographic region of Earth’s seas, comprising the tropical waters of the Indian Ocean, the western and central Pacific Ocean, and the seas connecting the two in the general area of Indonesia. It does not include the temperate and polar regions of the Indian and Pacific oceans, nor the Tropical Eastern Pacific, along the Pacific coast of the Americas.” Strategic analysts on the other hand delimit the Indo-Pacific arena as stretching from the Indian Ocean, (bound by the east coast of Africa) through the equatorial seas around the Indonesian archipelago, the South China Sea, all the way to the Pacific Ocean (bound by the west coast of North America). The term recently emerged in strategic discourse as a substitute for the more established Asia Pacific with the renaming of the US Pacific Command (PACOM) as the US Indo-Pacific Command (IPACOM). While this change could be merely symbolic, reflecting the reality of the area that the command was responsible for anyway, the possibilities of the extension of IPACOM to the east coast of Africa remains a distinct possibility and assumes strategic relevance.

The Indian rhetoric is based on the inter-connectedness of the Indian and Pacific Oceans, the importance of oceans to security and commerce and India’s role within the broader region. This was articulated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi during the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore, where he clarified that this was neither a strategy nor an exclusive club. He described it as a “natural region” ranging “from the shores of Africa to that of the Americas” and argued that it should be “free, open, and inclusive”; grounded in “rules and norms…based on the consent of all, not on the power of the few”; and characterized by respect for international law, including freedom of navigation and over flight. He went on to stress that it was not in conflict with ASEAN unity and centrality. While the articulation of the Indo-Pacific as a strategy to balance Chinese influence over the oceans was implicit in this discourse, the downplaying of the concept by the Chinese is a clear indication that the openness of the policy is in contradiction to their policy in stretches like the South China Sea. In response, the number of strategic dialogues, intelligence sharing mechanisms, military exercises, and defence compacts involving large and medium powers in the Indo-Pacific — including India — have rapidly multiplied.

The twenty-first century Maritime Silk Road (MSR) was proposed by Chinese president Xi Jinping in October 2013 during a speech to the Indonesian Parliament. The route of this Maritime Silk Road goes through cities of Guangzhou, Fuzhou, Guangzhou, Haikou, Beihai, Hanoi, Kuala Lumpur, Jakarta, Colombo, Kolkata, Nairobi, Athens and Venice. The maritime areas of this Maritime Silk Road include the East China Sea, South China Sea, the Indian Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. Indian strategic thinking identifies the Maritime Route as a repackaging of the ‘string of pearls’ strategy, a position reflected in C. Raja Mohan’s Samudra Manthan, Sino-Indian Rivalry in the Indo-Pacific (2012) where he argues that that the land competition between China and India will spill now out to the ocean and the Indo-Pacific is becoming a new geographical space for this contest.

The Indian alternative has been to focus on the eastern and western reaches of the Indian Ocean and the sub continental landmass south of Eurasia but linked to it. The development of a network of Indian Ocean ports to serve as regional shipping hubs for littoral states with connecting highways and rail routes would mean leveraging India’s location in one of the most strategic stretches of ocean space. The launching of a Spice Route, Cotton Route and the Mausam Project, all of which are attempts to tie together countries around the Indian Ocean assumes significant in this context. At the macro level the aim of Project Mausam is to re-connect and re-establish communication between countries of the Indian Ocean world which would lead to enhanced understanding of cultural values and concerns while at the micro level the focus is on understanding national cultures in their regional maritime milieu. The aim is not just to examine connections that linked parts of the Indian Ocean littoral but also the connections of these coastal centers to their hinterlands. The ‘Spice Project’ aims to explore the multi-faceted Indo-Pacific Ocean World collating archeological and historical research to document the diversity of cultural, commercial and religious interactions in the Indian Ocean- extending from East Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, the Indian sub-continent and Sri Lanka to the Southeast Asian archipelago. The broader aim is to connect these with ‘Information Silk Route’ where telecom connectivity between the countries would be made possible. Partly propelled by the advancement in informational technology in India and partly by the fact that connectivity on the ground has been restricted by political connections these strategies need to be visualized as integrated aspects of both domestic and foreign policy.

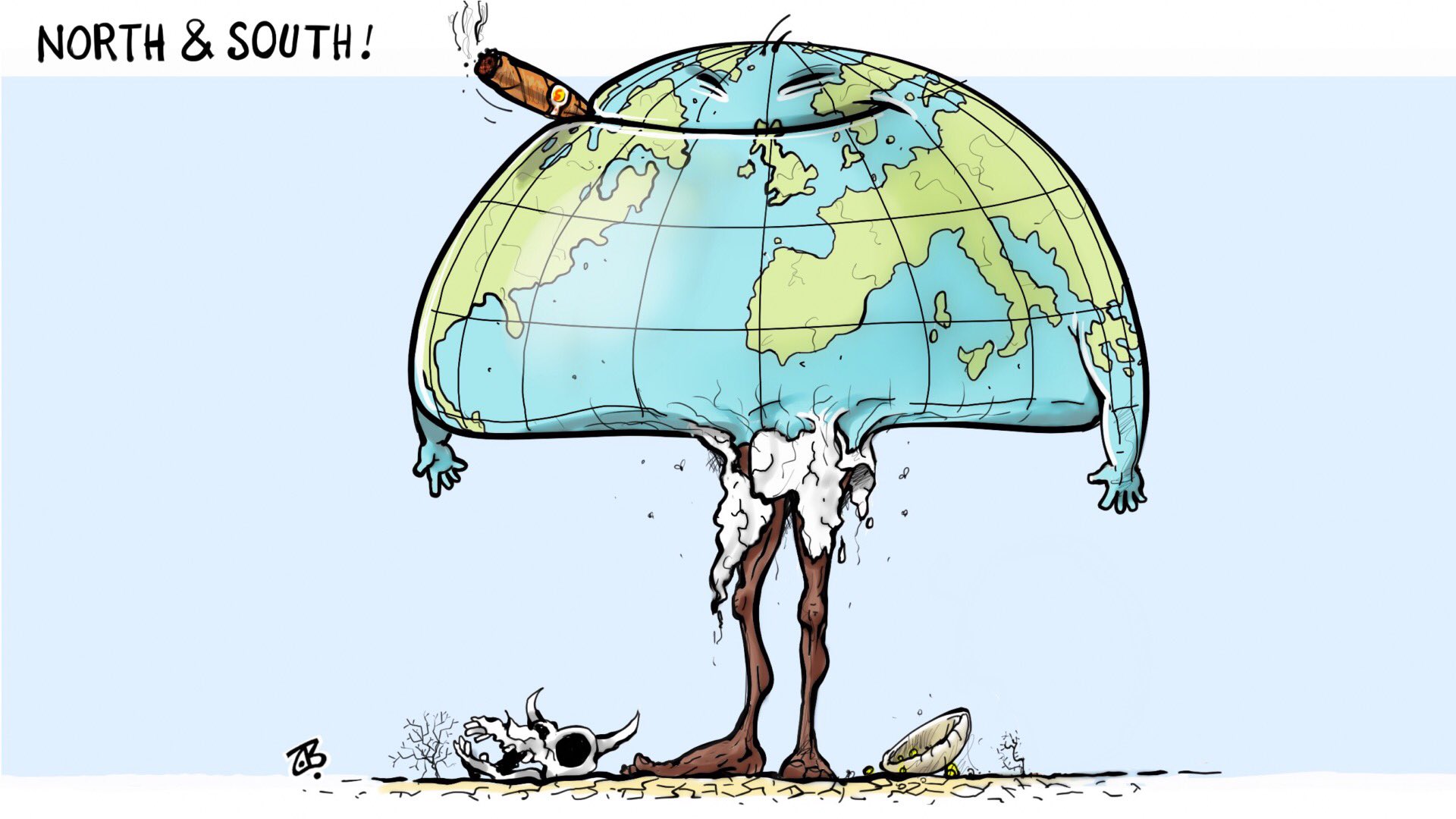

In a recent article, Samir Saran (“Eurasia: Larger than Indo-Pacific – Liberal world must stand up and be counted, or step aside and watch Pax Sinica unfold”, Times of India, 4 June 2018) however, argues that efforts to shift global centrality to the ‘Indo-Pacific’ remain an insufficient response to China’s spectacular measures to connect Europe and Asia. Reiterating Macinder’s position he contends that Eurasia remains the ‘supercontinent’ and the new world order will be defined by who manages it and how it is managed. It is in this supercontinent that the future of democracy, of free markets and global security arrangements will be decided. Having assessed that the divide between Europe and Asia is artificial, China has moved towards the creation of a network of connectivity projects that have diluted the significance of sub-regions and upset power arrangements. He argues that an open Indo-Pacific vision is an insufficient response to China’s relentless pursuit of building infrastructure, facilitating trade and creating alternative global institutions across Eurasia.

Nicholas Spykman once observed that ‘Every Foreign Office, whatever may be the atlas it uses, operates mentally with a different map of the world’. For the modern Indian state, it was recognized from the start that India was geopolitically located at the crossroads of several sub-regions. In Nehru’s words “India is situated geographically in such a way that we just cannot escape anything that happens in Western Asia, in Central Asia, in Eastern Asia or South-East Asia.”. A rejuvenated China has negotiated what will probably be a decades-long process of constructing new lines of communication to the sub-regions of Asia. For China, it is incidental that India lies on the crossroads of Chinese Silk Routes. For India, however, this dynamic holds the potential to reshape its entire periphery and impact India’s own role in Southern Asia calling for enhanced engagement and expanded presence.

Anita

10th June 2018

Leave a Reply