‘Summitry’: From Munich to Mamallapuram

Posted on : November 11, 2019Author : AGA Admin

Informal Summits are increasingly being recognized as an innovative contribution to global diplomacy. It is being argued that by not setting expectations or deliverables informal summits allow for the possibility of positive long term effects that formal meetings following protocols and a definite agenda often do not. ‘Summitry’, defined as the art or practice of holding a summit meeting, specially to conduct diplomatic negotiations was recently in news following Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s informal summit with Chinese President Xi Jinping at Mamallapuram on 11-12 October 2019. However, informal summits, as David Reynolds in his book Summits: Six Meetings that Shaped the Twentieth Century(Allen Lane 2007) argues is as ancient as the meetings between kings and emperors. They have only been made imperative in recent times by air travel, weapons of mass destruction and publicized by an all pervasive new mass media.

According to Reynolds, the word ‘summit’ was introduced in international parlance in the 1950’s by Winston Churchill, who wanted to use ‘parleys at the summit’ to defuse the Cold War. The decade of the 1950’s and 1960’s proved too unpredictable, so it was not till the era of détente that leaders felt that they should meet to develop mutual understanding. Reynolds describes six summits that shaped the twentieth century beginning with Chamberlains’s meeting with Hitler in Munich in 1938, followed by Khrushchev and Kennedy’s meeting in Vienna in 1961, Reagan’s summits with Gorbachev in 1985 and the Camp David Summit between Sadat, Carter and Begin. The stories of these summits along with the Yalta Conference and the Nixon-Brezhnev meeting in 1972 reveal the intentions that made the summits risky but also occasionally productive.

What makes the book interesting is Reynold’s analysis of why some summits bolstered international harmony and others did not. According to Reynold’s the least successful are ‘personal’ summits like the 1938 summit between Hitler and Chamberlain and the 1961 Kennedy Khrushchev encounter, where the leaders sought to ease international tensions by establishing personal rapport and using their individual powers of persuasion to get their way in disputed matters. Somewhat more successful were meetings that Reynold’s terms as ‘plenary summits’ In these like the 1945 Yalta Summit and the Camp David summit on the Middle East, heads of state relied on a large team of advisors and focused on solving specific problems through exhaustive bargaining. Reynold’s argues that such summits resulted in numerous agreements but also that most of the deals were not fully implemented as they were not rooted in genuinely cooperative relations between states that were a part of the agreements. By far the most successful meetings, according to Reynolds were ‘progressive summits’. These summits exemplified by the US-Soviet Summits of 1972 and 1985 involved features of both. Leaders sought to build personal rapport and reach specific agreements with the help of expert advisors. However, what set them apart was the understanding that these summits were part of a long term process of building trust and resolving disagreements at their roots.

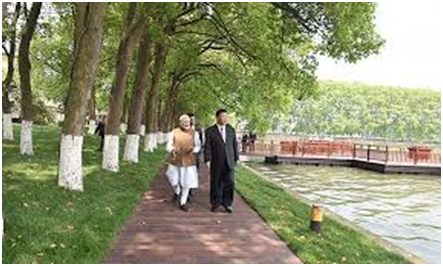

The second Modi-Xi Summit was held at Mamallapuram, a port city near Chennai that had ancient trade links with China. The timing of the summit, following China’s internationalization of the Kashmir issue in the aftermath of the revocation of Article 370 was also significant. Though the informal summit was aimed at exchange of ideas between the two leaders, without any formal pre-determined agenda, it was expected that there would be agreement on new security measures along the line of control. The aim of the summit was to prevent further deterioration in relations and move forward on a set of confidence building measures particularly in terms of border disputes. As such it was part of the more than twenty rounds of Sino-Indian meetings on the issue at various levels.

The Summit was also meant to cement the gains of ‘strategic communication’ that followed the Wuhan Summit held in the backdrop of the highly volatile 73-day Doklam standoff in 2017. The Wuhan summit involved ten hours of conversations between the two leaders on three broad themes: domestic developments and direction of each state; how each state viewed the world and recent global and international developments; and the state of the India-China bilateral relationship. Emerging from the Doklam standoff, both ‘issued strategic guidance to their respective militaries to strengthen communication in order to build trust and mutual understanding and enhance predictability and effectiveness in the management of border affairs.’ The Summit led to the much talked about Wuhan spirit embodying the consensus that the leaders had reset the direction of the relationship. Another substantive outcome was the China-India model, a forward movement on the BRI that India has objected to since its inception on grounds that it violated its sovereignty pointing to segments like the CPEC. The period following Wuhan saw a better, faster communication that prevented border skirmishes and scores of regular, cordial bilateral meetings betweenPrime Minister Modi and President Xi at the sidelines of multilateral summits like the SCO.

At Mamallapuram President Xi was accompanied by distinguished diplomat Wang Yi while Prime Minister Modi’s team included External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar and National Security Advisor Ajit Doval. And the one to one meeting between the leaders was followed by delegation level talks between the two sides.The leaders’ commitment to improve trade relations for instance was followed by a decision to set up a new high level economic and trade dialogue mechanism. The optics that the summit generated and the cultural perceptions and expectations wereequally significant. After a ceremonial welcome President Xi was taken on a tour of three iconic monuments — Arjuna’s Penance, Panch Rathas and the Shore Temple where the leaders watched a cultural programme followed by a private dinner for President Xi hosted by Prime Minister Modi. The symbolism of the personal tour and the informal one to one meetings was beamed across national channels pointing to the fact that at a personal level the two leaders were comfortable with each other. At the conclusion of the Summit President Xi noted that he and Prime Minister Modi had ‘engaged in candid conversations like friends and heart to heart discussions on bilateral issues’.While no formal statement was issued communications from both sides following the Summit was positive.

Successful summits are fundamentally dependent on whether the leaders share a basic belief. For instance, the success of the Reagan Gorbachev summit was principally because of a shared belief that the nuclear arms race could be curbed. It was argued that a shared belief in a rules based multilateral trading system and commitment towards open and inclusive trade arrangements could provide the impetus for the transformation of the Modi-Xi Summit from ‘personal’ to ‘progressive’. As such it could have been assumed that the meeting would be followed by India’s entry into the multilateralRegional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, China’s alternative to the Trans Pacific Partnership.

That structural problems can rarely be addressed by informal summits became evident when the Indian government postponed the signing of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership,identified by China as one of the six issues that were of fundamental and mutual interest between the two states in a statement following the Chennai Summit. While Prime Minister Modi had stressed the importance of ensuring that the RCEP was balanced in terms of trade in goods, services and investment even during the Summit, it was also true that India’s decision was largely in response to fears of a surge in imports from China, affecting the ‘Make in India’ project launched across 25 sectors of the Indian economy and opposition from Indian farmers and small businesses. In a move that has been identified as a strategic shift immediately following the postponement, Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal remarked that India was exploring trade agreements with the US and the European Union where ‘Indian industry and services will be competitive and benefit from access to large developed markets.’

While this should not be identified as amounting to a crisis of Sino-Indian ‘summitry’ it is definitely an indication that domestic legitimacy and accountability remains pivotal in politics.It is also probably an indication of the fact that summitry is coming of age and future summits will increasingly be a place where diplomacy at the highest level would need to meet public concerns and interests of domestic constituencies.

Anita Sengupta

8 November 2019

Leave a Reply