Social Budgeting in India: Challenges and Approach

Posted on : March 8, 2022Author : Aniruddha Mukhopadhyay

This paper analyses the flow of receipts and expenditures in the Indian social sector at all governmental tiers. To find meaningful trends, data has been gathered from secondary sources including economic surveys, budget reports, quantitative research, and academic texts. India’s social spending is underperforming relative to national targets and international standards. The study highlights the dependency of subnational social sector expenditures on fiscal transfers from upper tiers. Unlike the counter-cyclical nature of capital expenditures, recent trends of budget allocations observed in the Indian social sector and its flagship programmes show pro-cyclical tendencies. The study also finds that the lack of fiscal autonomy, fall in receipts and rising costs of healthcare have increased the fiscal stress on Local Governments which in turn has contracted their social spending.

Social Budgeting is the financial statement of the accounted and estimated total of receipts and expenditure for the social sector of an economy. In India there is no practice of presenting a budget for the social sector as separate from the single annual budgets prepared by the different tiers of government. This writing therefore mainly focusses on the flow of receipts and expenditures in the Indian social sector. The social sector is associated with activities related to the development of human capital, equitable distribution of welfare and the delivery of public goods. In India, the social or so-called development expenditure is categorized under two major heads – social and economic services. Social services comprise of (a) education, sports, art and culture, (b) medical, public health and family welfare, (c) water supply and sanitation, (d) housing, (e) urban development, (f) welfare of SCs, STs and OBCs, (g) labour and labour welfare, (h) social security and welfare, (i) nutrition, (j) relief on natural calamities and (k) others. Economic services include agriculture and allied activities, energy, rural development, irrigation and flood control, transport and communication, science technology and environment, industry and minerals, special area programmes, and general economic services.

Spending on social services like education, healthcare and social security is essential for the development of human capital which in turn generates growth in the long term. Social expenditures, especially social security or safety nets protect the disadvantaged sections of society from the adverse impacts of economic crises and slowdowns, and help in reducing income inequalities.

According to the federal distribution of expenditure responsibilities given by the VII Schedule, most of the social services fall under the responsibility of State governments. Indeed, almost 80 percent of total Centre-State public expenditure on social services is incurred by State governments (State Finances: A Study of Budgets, Reserve Bank of India). However, States receive fiscal transfers from the Centre to finance centrally sponsored schemes and bridge the vertical tax imbalances. The Centre to State fiscal transfers include the grants and proceeds of sharable taxes supervised by the Finance Commission and the Plan transfers supervised by the NITI Aayog. According to the revised estimates of subnational revenue collection in 2020-21, central transfers comprise almost 48% of the total revenue receipts of State Governments and UTs. States with lower per capita GSDP (Gross State Domestic Product) have a higher dependency on fiscal transfers for financing their public expenditures in general and social expenditures, in particular.

The Social Performance of Economic Growth

Health and education are the major components of social sector allocations and usually comprise 60 per cent of total social service expenditure. Both categories have witnessed YOY increases but still remain dangerously lower than expected standards at national and international levels. According to the latest Economic Survey for 2021-22, combined Centre-State allocations for education stagnated at 3.1% of the GDP for two consecutive years hence failing the target of 6% set by the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 and all previous education policies since 1968. As percentage of the combined Centre and State expenditures, education showed a downward trend from 10.8% to 9.7% between 2014-15 and 2021-22 Budget Estimates (BE). As for health sector, the expenditures increased from 1.8% to 2.1% of the GDP between 2020 and 2021. Overall, the BE of combined Centre-State expenditures on the social sector was 8.6% of the GDP in 2021-22.

In 2019, India was surpassed by its south Asian neighbours Nepal, Bhutan and Maldives which turned 7.5%, 9.9% and 14.8% of their GDPs respectively, to social expenditure while for India it was only 6.3%. The regional average of social expenditure as percentage of GDP was 5.22 for South Asia, 7.74 for East Asia and Pacific (EAP), 7.93 for the Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), 8.58 for Middle East and North Africa (MENA), 9.85 for Latin America and Caribbean (LAC), and 14.31 for Europe and Central Asia (ECA). The World average was 12.19 per cent which is bound to have increased since 2019 (Bloch, C. 2020).

Cyclicality of Social Sector Expenditures:

India’s subnational Social sector expenses in the period 2000 to 2012-13 have been mostly counter-cyclical i.e. negatively correlated with the real income of subnational governments (Balbir Kaur, Sangita Misra and Anoop K. Suresh, 2013). This reflects that spending in social sector has decreased in times of economic growth while a certain amount of downward rigidity has been maintained to protect social spending during recessions or slowdowns. A positive takeaway is that social spending has not been compromised for but conjoined with India’s fiscal strategies that counter slowdowns by increasing public sector expenditures, cutting taxes, and maintaining growth trajectories. Lately however, public expenditures in social services haven’t maintained their stability at the face of economic crises, evident in the ongoing experience of the pandemic during which the social sector underwent several budget cuts.

Trends of Social Expenditures across Recent Union Budgets:

On the expenditure profile of a Budget, revised estimates (RE) that are lower than the budget estimates (BE) may indicate cut back on expenses, lower benefits delivered or reduced coverage of beneficiaries. Large differences between the BE and RE do not reflect well on either the benefit incidence of public expenditures or the accuracy of budgetary estimates. These large gaps may also indicate that significant shares of allocated ministerial funds remain unutilized. Conversely, a revised decrease in budget estimates can also occur due to a shortfall of revenue receipts thus indicating poor resource mobilization capacities at any level of governance.

In the 2021-22 Union Budget, the Centre reduced the estimated budget for education expenditures by ₹6087 crores from that of the previous year within which ₹4972 crores and ₹1115 crores were deducted from the funds allocated for school education and higher education, respectively. According to the 2022-23 Union budget, out of the total ₹99311 crores BE for education in 2020-21, only ₹84218 crores was actually spent. While these reduced expenditures run parallel to a national education emergency characterized by higher drop outs and rising unemployment during the pandemic, the GoI has argued that the reduction in education expenditures enabled the flow of funds to social security, healthcare, and capital expenditures that are supposed to recover the economy through long term multiplier effects. Although the estimated funds allocated to the Department of School Education and Literacy increased in 2022-23, a substantial portion of funds was cut from the PM POSHAN Scheme (formerly called National Programme for Mid-Day Meal in Schools), a principle scheme under the parent Ministry of Education. The BE for the scheme reduced from ₹11500 crores in 2021-22 to ₹10233 crores in 2022-23. The latest allocated fund is further lower than the amount spent in 2020-21 (₹12878 crores) which is strange considering that schools weren’t open then but they are now.

In the segment of Medical and Public Health and Family welfare, while the Centre has consistently increased its budget allocations since the beginning of the pandemic, the State governments have severely underperformed. The total expenditure of States and UTs was 5.5 % of the aggregate subnational expenditure and only 1.1% of the GDP. Despite exceeding the pre-COVID levels, the subnational expenditure on healthcare was 6.6% of their primary expenditure in 2021-22 which is still lower than the target of 8% set by the National Health Policy 2017.

The Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) is a centrally sponsored scheme implemented at the subnational level and aimed at immunization, pre-school education and nutritional support to children. The programme underwent substantial cut backs on its allocated funds in the 2022-23 budget. In 2020-21, only ₹18204 crores was actually spent out of the total BE of ₹28557 crores. The Umbrella ICDS programme was integrated into the Saksham Anganwadi and POSHAN 2.0 Scheme, the BE for which increased by a mere ₹200 crores in the latest budget. The Ministry of Women and Child Development which directs the programme also experienced a cut back on its expenditure allocations despite the levels of malnutrition being higher than pre-Covid period. The reduced funds come at a time when the data revealed by the National Family Health Survey-5 on November 24th, 2021 show levels of severe wasting in children under five due to malnourishment – the percentage of the affected children increased from 7.5% in 2015-16 to 7.7% in 2019-21. Furthermore, several of the Anganwadi set ups which implement the ICDS scheme have been closed, requiring Anganwadi workers to help the government in Covid-19 relief programmes.

Certain areas however saw massive increases in allocations. For example, the RE for the Department of Food and Public Distribution in 2020-21 was ₹316,413 crores higher than the BE i.e. RE was 258% of BE. The following year allocations were double that of the preceding budget estimate, and the revenue estimates were even higher – this was mainly due to the various stimulus packages introduced by the GoI to offset the impacts of COVID-19, notably the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY). The programme delivers 5 kg of wheat/rice per month free of cost to 80 crore households identified as National Food Security Act (NFSA) beneficiaries.

Another such department is that of Drinking Water and Sanitation, the BE for which spiked from ₹21518 crores to ₹67221 crores between 2020-21 and 2022-23. This increase was mainly due to the Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM), the BE for which entailed an increase of almost ₹49,000 crores over the actuals of 2020-21. The allocations for JJM overlap with other segments like the supply of drinking water, tap water and sanitation in schools, healthcare units and so on.

MGNREGA:

Launched in 2005, The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee (MGNREG) Programme is a centrally sponsored scheme that provides guaranteed wage employment of 100 days in every fiscal year to one adult member of every rural household.

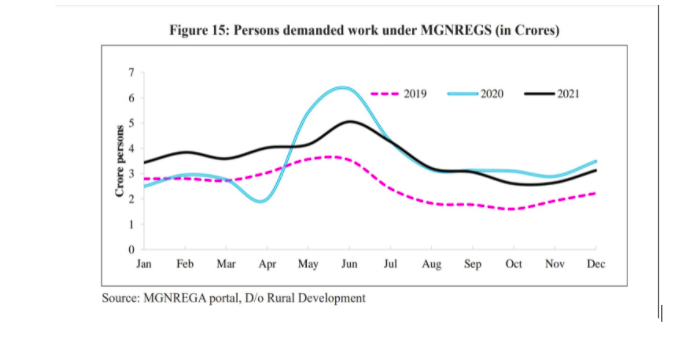

The RE for the scheme has almost always been higher than the BE hence indicating that the demand for guaranteed work always exceeds its supply. In 2020-21, the RE for the Scheme surpassed its BE by a massive ₹50,000 crores, mainly due to the surge in demand for work among the migrant labourers returning to their source States. Despite an actual amount of ₹111,169 crores being spent on the programme in 2020-21, the BE for the next year was kept at ₹73,000 crores. Quite inevitably it was exceeded by the ₹98000 crores of RE, again indicating a surplus of demand. Refusing to respond to this continuous trend, the Centre has yet again kept the BE for the Scheme at a static amount of ₹73000 crores in the 2022-23 Union Budget – a cut back of 25.2% from the RE of the previous fiscal year. The cut backs are highly incongruous to the present reality of the rural labour market. According to the latest Economic Survey 2021-22, during the second wave of the pandemic in India, the demand for the guaranteed employment reached a record high of 4.59 crore individuals in June 2021. Even after adjusting for the seasonality of such trends, the demand is substantially higher than the pre-pandemic levels of 2019.

Is Social spending really Revenue Expenditure?

Almost the entirety of the actuals and estimates on the expenditure accounts of social sector budgets are categorized as revenue expenditures and not capital outlay. There are two fundamental problems of identifying social sector expenditures as revenue expenditures. First, investments on human capital aren’t just operational costs but also promise long term growth through proper distribution of income, up skilling of labour, and tapping of demographic dividends. To quote C.P. Chandrashekhar, an economist with the Delhi-based think-tank Economic Research Foundation, “In the long-term, social sector spending creates social and economic capital. So, terming them revenue expenditure is not sensible”. The bigger problem with this misidentification lies with the policies of fiscal consolidation that put strict limits on the permissible levels of revenue deficit for both the Centre and the States. Consequently, governments at different tiers have to restrict their social sector spending within the low statutory limits of revenue deficit while their infrastructural and commercial investments are allowed significant space for debt-financing. In fact many of the State governments have reduced their spending on social services on account of reducing their revenue deficits and complying with State level Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Acts.

Resource Mobilization and Allocation:

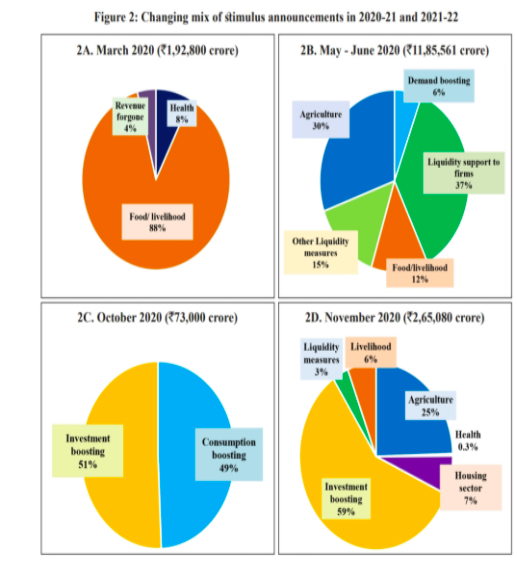

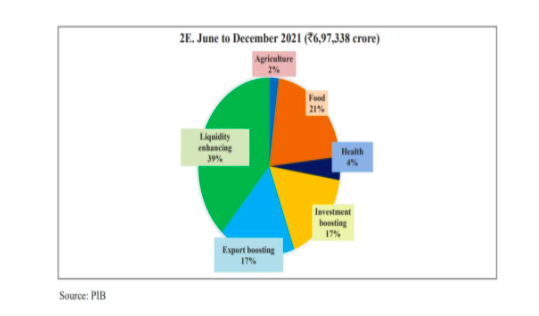

The revenue collection performance of the State is an essential pre-requisite of its ability to finance its expenditures. Moreover, federal structures like that of India in which the annual budgets are integrated with the Planning process, the surplus on the revenue account of the Budget is the first major source of the funds required for capital expenditures. Furthermore, tax must increase at rates greater than that of income growth in order to finance infrastructural investments and social welfare, beyond meeting operational costs. According to the Economic Survey 2021-22, net tax revenue to the Centre, which was expected to grow at 8.5 per cent in 2021-22 BE relative to 2020-21 PA, grew at 64.9 per cent during April to November 2021 over April to November 2020 and at 51.2 per cent over April to November 2019. If social sector saw budget cuts at revised stages of 2021-22 and there wasn’t a revenue shortfall to explain that then where exactly was the augmented tax reserve allocated? In between the beginning of the pandemic in 2020 and December 2021 the GoI announced stimulus packages across different sectors in order to provide relief from the impacts of COVID-19. These announcements were done in 5 phases – March 2020, May to June 2020, October 2020, November 2020, and June to December 2021. In the first, fourth and fifth of these phases in which health sector did receive allocations, the share of its funds vis-à-vis the other sectors was 8%, 0.3%, and 4% respectively. The fiscal policy that the GoI adopted in response to the pandemic was an initial provision of safety nets followed by an exclusive focus on “more productive capital expenditure”, mainly in infrastructure, that are “expected to collectively generate employment and boost output in the medium to long term through multiplier-effects” (Economic Survey 2021-22).

Local Governments, Pandemic and Fiscal Stress:

A discussion on social expenditures would be incomplete without the due consideration of the role that local governments played in fighting the pandemic.

While all governmental tiers came together to tackle COVID-19, it were the Local Governments that performed additional responsibilities like “setting up make-shift hospitals and quarantine centres; contact-tracing; ramping up testing facilities; distribution of free food to the poor; information dissemination; implementing travel restrictions; fostering COVID-appropriate behaviour among the public; maintaining the supply of essential goods and services; and organising vaccination camps while simultaneously addressing vaccine hesitancy issues” (Coping with the Pandemic: A Third-Tier Dimension, 2021).

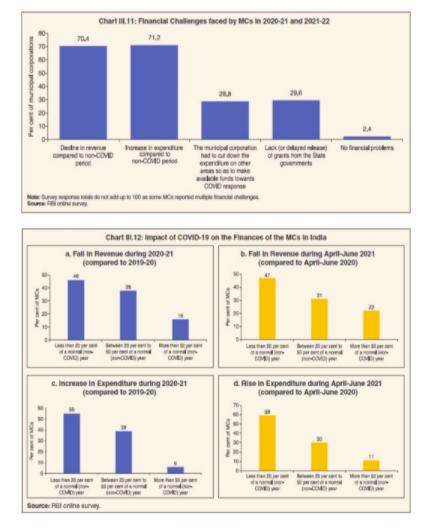

Simultaneous to its enlarging set of responsibilities, Local governments (LG), especially Municipal Corporations (MC), experienced the steepest fiscal stress during the pandemic amongst all federal tiers. This was due to a combination of factors – falling revenue receipts, rising costs of healthcare and pandemic-related expenditures, and lack or delayed release of funds from State governments. It was estimated that LGs lost 15-25% of their revenues in 2021 (Wahba et al. 2021). According to data collected from 20 large MCs that accounted for 60 % of total receipts and 55% of total expenditure of all MCs in 2017-18, the RE of tax receipts reduced by 16.3 % over their BE in FY2020-21. On the expenditure profile of these MCs, revenue expenditures which include social sector expenses comprise two-thirds of total cash disbursements. Of this revenue expenditure, more than 50 % is spent on establishment expenditures like salaries, wages, bonuses, and pensions. In 2020-21, the revised estimates of expenses on establishment decreased by 13.1%, within which salaries, wages and bonus declined by 16.1 % from the budget estimates. Overall revenue expenditure reduced by 6.6% at the revised stage indicating that MCs had to cut down expenses to balance the revenue shortfall.

The fiscal stress on the third tier is aggravated by the fact that local governments aren’t statutorily allowed to run a deficit and their budgets must always maintain a surplus of revenue receipts over revenue expenditures. The rationale is that a large portion of the local governments’ receipts come from upper tiers, indicating a lack of fiscal autonomy. The 15th Finance Commission announced a reduction of Central transfer of grants to local government bodies including the grants for health sector from ₹90000 crores in 2020-21 to ₹80207 crores in 2021-22 (economic survey 2021-22) Furthermore, most areas of local expenditures are ‘committed’ or inelastic.

To further strengthen the causal relation between the fiscal health of local governments and their ability to deliver social services, a cross-sectional regression of district vaccination rates on the fiscal health of municipal corporations was conducted by the staff of RBI between February-October 2021. Having adjusted for other variables like the varying infection rates across different districts, the empirical outcome observed was that the MCs with higher per capita receipts (income) registered higher vaccination rates. These findings prove why it’s essential to improve the fiscal health of India’s first point of contact with its people.

Conclusion:

It is clear from the above discussion that although India’s aggregate social sector spending has increased annually and has maintained an overall counter-cyclical rigidity at the face of economic slowdowns, the newly reinstated focus on long term capital expenditures comes at the backdrop of cut backs in several segments of the social sector expenditure; rendering a more pro-cyclical trend during the pandemic. Furthermore, the pressures of complying with strict ceilings of revenue deficit and high dependency on fiscal transfers for financing social services at subnational levels lead to further contraction of the fiscal space available for the social sector. Ultimately, India’s expanding social sector is still underperforming relative to regional and international standards.

References:

- Economic Survey 2021-22, Government of India, Ministry of Finance, Department of Economic Affairs, Economic Division, January 2022

- State Finances: A Study of Budgets of 2021-22, Reserve Bank of India, November 2021

- Kaur, B. Misra, S. and Suresh, A.K. (2013) Cyclicality of Social Sector Expenditures: Evidence from Indian States. Reserve Bank of India Occasional Papers, Vol. 34, No. 1 & 2: 2013

- Sury, M.M. (2009) Budgets and Budgetary Procedures in India: 1947-48 to 2009-10. New Century Publications, New Delhi, India.

- Bloch, C. 2020. Social spending in South Asia: an overview of government expenditure on health, education and social assistance. Research Report No. 44. Brasília: International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth and UNICEF Regional Office for South Asia.

- Expenditure Profile 2022-23. Government of India, Ministry of Finance, Budget Division, February 2022

- Expenditure Profile 2021-22. Government of India, Ministry of Finance, Budget Division, February 2022

- Expenditure Profile 2020-21. Government of India, Ministry of Finance, Budget Division, February 2022

Author:

Aniruddha Mukhopadhyay

Intern, Asia in Global Affairs

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the text belong solely to the author, in his personal capacity. It does not reflect the policies and perspectives of Asia in Global Affairs.

Leave a Reply