Restored Currency Building in Kolkata transformed into Unique Cultural Hub

Posted on : January 20, 2019Author : AGA Admin

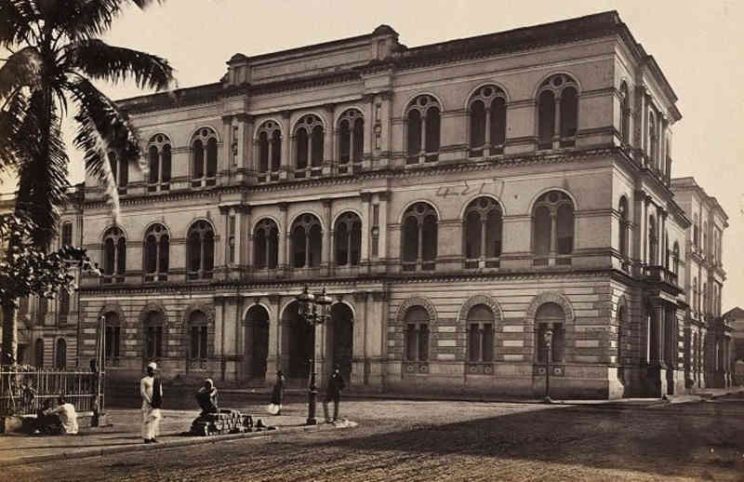

Among Kolkata’s remaining gems of colonial architecture that once celebrated the old capital of British India, the Currency House deserves special mention. In 1772, after the East India Company was abolished, Calcutta became the capital with Warren Hastings, the first Governor General. It remained the capital till 1911, and was regarded as the second city of the British Empire, second only to London. It was not only the administrative capital; it was also the central hub of finance and international trade. There was a flurry of grandiose construction undertaken from the late 1770s to the 1830s as befitted the prosperity and prestige of this seat of colonial power. If to impress and to awe was the intention then the Governor’s palace, The Governor’s fishing tank, the Lal Dighi, and the surrounding buildings including the Currency House certainly achieved the objective.

The website of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), the custodian of the Currency Building, says that the building was “founded in 1833” and first housed the Agra Bank. The building got its present name when “the government occupied a large portion of it for its Currency Department in 1868 from the Agra Bank Limited”. It was a beautiful three storied brick building constructed in the Italian style. The roof was arched with iron joists and the floors were covered in Italian marble and Chunar sandstone. The Italian architecture was unique and a rarity. Most of the other buildings constructed during the time were more Gothic in style. The central hall received sunlight from skylights topping the large domes. When the resources of the Agra Bank became restricted, the bank sold the larger part of the premises facing the Lal Dighi or Dalhousie Square to the government and the Agra Bank withdrew to the rear part of the premises with its entrance on Mango Lane. The Currency Department was formed for issuing government currency notes after the passing of the Paper Currency Act in 1861. To house the department the government purchased the building for the princely sum of Rs1, 073, 109

.

Till 1937, the building served as the first office of the Reserve Bank of India. Archaeologists have come across evidence of an underground canal from the river Hooghly through which water was channelized to cool the freshly minted coins. Several vaults were built to hold currency, evident from the thick iron sheets covering not just the walls, but also the floors and even the roof of such rooms.

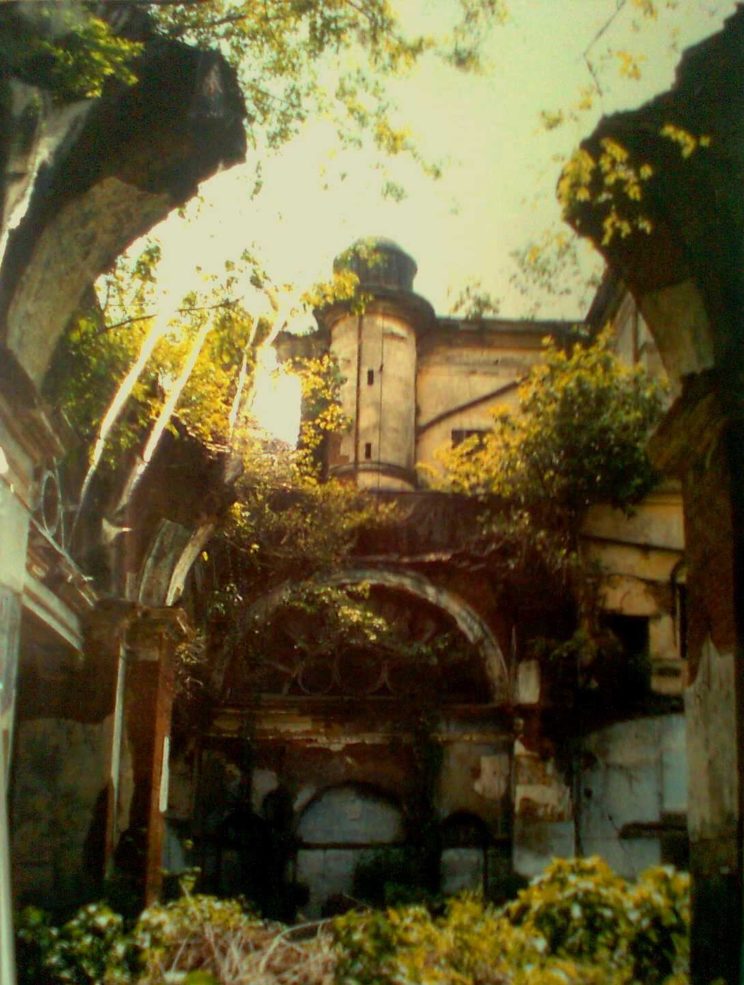

The building remained in use till 1994. Despite its architectural and cultural significance it was neglected for years and fell into decay. It was even used as a storehouse by the Central Public Works Department until in 1996 when the building was declared unsafe and demolition began. Luckily it came to the attention of the Indian National Trust for Art & Cultural Heritage, and INTACH intervened along with the Kolkata Municipal Corporation to prevent further damage. In his book White and Black, Soumitra Das lists the damages. He writes, “In between 1998 and 2003, the building did not only lose its three domes, the barrel vault, the single-storey portion on the southern side, the northeastern first floor on the eastern side and the joists, but it also lost its valuable Italian marbles, Burma teak furnishings, iron chests whose estimated cost would be over Rs 2 crore.”

The Archeological Survey of India was given charge in 2003 but could only take over in 2005. Since then there has been extensive and detailed restoration and reconstruction. Now it is all set to gain recognition as an exhibition hub.

The National Jute Board of India held the first exhibition in the restored building from January 7th to 10th. Called Artisan Speak, A Textiles Outreach Initiative – 2019, it showcased a delightful display of handlooms and master artisans from all over India over three floors. The exhibition was inaugurated by Smt Smriti Irani, Union Minister for Textiles, and Sh Ajay Tamta, the Minister of State for Textiles. There was also a fashion show on one of the days held in the open courtyard which was once the domed Central Hall. The exhibition was open to the public for the last two days and for those who managed to go, it was a wonderful opportunity to marvel at the intricate wrought iron canopy at the entrance, the chequered italian marble floors, the green Venetian tiles, the handsome wooden staircase, and the lofty proportions of the corridors. The jagged edges of the pillars of the open courtyard, left exactly the way it was when the domes were demolished just adds to the drama. The hard work and detailing that has gone into the building’s restoration and conservation is truly commendable. One hopes that this successful endeavor will lead the way to more awareness of the need to preserve the city’s rich cultural heritage.

Prajna Sen

20th January 2019

Leave a Reply