Mrinmoyee “The Journey of Mritshilpa in Kumartuli from Sacred Rituals to Global Markets”

Posted on : April 15, 2024Author : Udita Ghatak

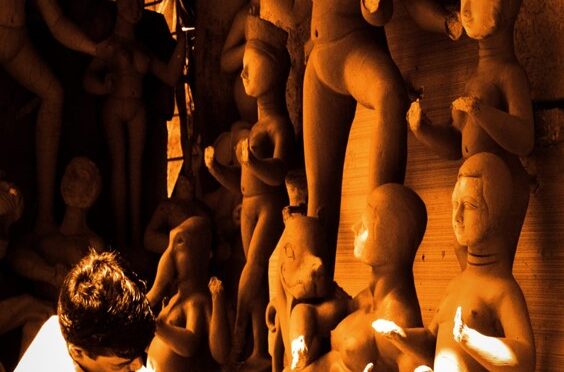

Stepping into the bustling lanes of Kumartuli, with every sunrise one finds a new rhythmic hum of artistic endeavour with the Mritshilpis (idol makers) , who from the gentle strokes of brushes carve out delicate features in their timeless works of beauty. Beyond its narrow alleys lined with mud idols and bustling home cum workshops, Kumartuli effortlessly blends the old and new to new tales of innovation and creativity. Kumartuli is a small neighbourhood of Kolkata, sandwiched between Ahiritola and Sovabazar in North Kolkata. Kolkata (erstwhile Calcutta) was the colonial capital of the Raj in British India on the banks of the Hooghly river. The spatial form of Kumartuli, as a working class neighbourhood, traces its origin to the specific kind of cultural expressions articulated in the city in the colonial days. Under the British, the city was divided into a white city, where the coloniser resided and a black city, where the native elite resided, with a grey city or zone of contact in between near Esplanade. Kumartuli, is located at the heart of the black city, dominated by the Zamindars or the landed gentry. During these days of the colonial era, the city was spatially organised according to an extension of the Jajmani system or the annual functional and occupational division of labour that lies at the heart of the Hindu caste order. This is how places like Kumartuli (land of the potters) or Colootola (land of the oil crushers) get their name from. Kumartuli till date, is a spatial form organised along the lines of caste, and it originates from the mass migration of the Kumbhakars caste of Krishnanagar, in the district of Nadia.

The presence of a number of settlements of the landed gentry like Sovabazar Rajbari, Jorashako Thakur Bari or Marble Palace are emblematic of this point. The festival of Durga Puja finds its origin in these houses of the native elite, before spilling out to the public realm in the form of Barowari Pujo. As the hegemony of the festival expanded in the public realm of the Bangali Bhadralok, the demand for Durga Idols increased, leading to the gradual emergence and consolidation of Kumartuli as a well organised space where Mritshilpis carried out their unbridled work. The spatial organisation of Kumartuli might externally look like a criss-cross of narrow alleys where the craft is carried out, but internally the art is carried out in a space which is organised along indexes like caste, gender and religion in an extremely stratified South Asian Society. This finds its reflection even in the Pratima or the idol. The disintegration of the idol from Bhanga Ekchala to Ekchala can be read as signifying a passage from the joint family to the nuclear family in provincial Bengal. In the immediate decades after the independence, and throughout the long impasse of the left front rule in West Bengal, there was a gradual loss of sponsorship from the elite, limited government initiatives for the benefit of the Mritshilpi, A lack of access to formal credit and loans, intensification of existing forms of social stratification etc, all of which collectively contributed to the gradual stagnation of the space. From a dynamic and bustling neighbourhood it gradually retreated into oblivion. Part of the problem was also because the successive state governments had taken active efforts of slum management, under a number of Development Plans, due to the over congestion of the city following the partition of Bengal. Due to these initiatives, parts of Kumartuli were marked as ‘slums’ by bureaucrats leading to a gradual neglect of Mritshilpa as a distinct form of art which required state endorsement and conservation. The neighbourhood of Kumartuli faced such a dismal condition until the LPG reforms of 1991 which marked a sea change in the life of the place, its people and the art.

Amidst the mud and colours, the mud craft of Kumartuli evolved from the realms of sacred ritual traditions of mud sculpting to a commercialised design industry set in motion by the twin forces of market and globalisation. and festivities after the reforms of 1991. The commodification of art with growing commercial demand is changing the practices of art and their stakeholders from artisans to artists. The formal relaxation on capital markets and labour regulations made it possible for foreign capital to directly interact with traditional arts like idol making in this case. With the rapid influx of foreign capital, interaction with the new middle classes and the new Bengali diaspora settled in the global west the Mritshilpi faces a scalar change in the festival of Durga Puja, or any puja for that matter as festivals became spectacles from the intimate affairs they used to be earlier. There was a gradual shift in the art also, as commercialisation of the festival led to the way it is celebrated. Specific pandals which were earlier intimate spaces are now sites of spectacles covering huge areas, cost, specific themes surrounding which it is designed, advertisements and billboards. Earlier the Pratima or the idol was made in the neighbourhood of the potters or Kumartuli, but contemporary forms of sculpture making require teams of Mritshilpis to set up virtual neighbourhoods for some months in a particular location for the making of a Pratima. On the one hand this to some extent is reducing the significance of Kumartuli as a neighbourhood, but also adding newer dimensions following the dispersal of global supply chains and commodity markets. Similarly, from ekchala or traditional forms of idols, contemporary idols also reflect a number of artistic influences like postmodernism or neorealism, due to the ever increasing global appeal of the festival as demonstrated by the recent UNESCO recognition given to Durga Puja. On the other hand the influx of corporate finance, foreign capital, and commercialisation has increased the real income of the traditional Mritshilpis, as a result of which some of them have gained significant upward social mobility while others are refusing to take up the same profession of their parents after getting educated. Hence while the reforms of 1991 is a defining moment, it is definitely the most complex conjecture in the history of this neighbourhood so far. While on the one hand the Mritshilpis can use it as a strategic moment to finally come out of systemic neglect, and gain upward social mobility this can also mean a gradual decay of the art. Similarly with the very nature of spatial arrangement changing from the Fordist days of assembly line production to a moment which has seen a massive dispersion of global supply chains, Kumartuli as a working class neighbourhood might be fundamentally redefined. The future of this place, which is a romantic retreat to every Bengali trying to take a stroll near Ahiritola ghat depends upon its articulation among these contradictions and is still open-ended.

Udita Ghatak,

Intern, Asia in Global Affairs.

The originality of the content and the opinions expressed within the content are solely the author’s and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the website.

Leave a Reply