Diasporas and Connects

Posted on : May 14, 2017Author : Admin2

The contemporary ubiquity of the diaspora as a focus of study is informed by dispersal of people on the one hand and new forms of connectedness on the other. The growth of interest in matters of global scope has led to a rethinking about spatial and temporal categories where not only the nation and its borders have been subject to scrutiny but also categories like regions and areas have come under interrogation. Amidst this re-thinking of spatial and temporal categories diasporas have gained currency as a productive framework for re-imagining locations, movements, identities and social formations. There has on the other hand also been an expansion of the term itself to include groups as disparate as ‘ethnics, exiles, expatriates, refugees, asylum seekers, labour migrants, queer communities, executives of transnational corporations and transnational sex workers’ moving beyond the more conventional understanding of the diaspora as a dispersed community or network oriented around a single point of origin. While Paul Gilroy’s evocation of the Black Atlantic world with its fractured movements and identities extended the study of the diaspora to an imaginative re-thinking of effects of migration, dispersal and displacement, rapid advances in technology has led to a spate of digital diasporas. There are therefore multiple ways in which trajectories and identities are being charted bringing into question terms like “Indian Diaspora” which brings with it the temptation to think of them as if they are stable bounded communities or transcendent homogeneous groups.

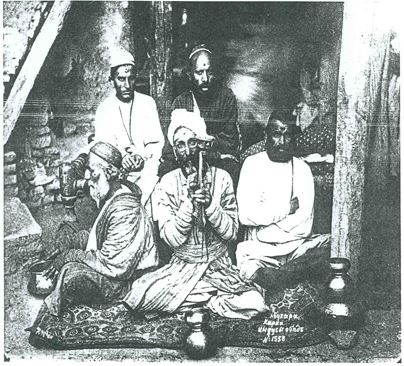

All of these issues of reifying, abstracting or generalizing come into play when one examines what would be identified as the “Indian” diasporic community in Central Asia. Close attention to the generic terms used here would indicate that traditionally groups and networks that could be termed as disaporic in the region were not all “Indian” in the contemporary sense. They were subsumed within the general term “Multani” “Khatri” or later “Shikarpuri” but were a conglomerate of different groups. Also movements of these groups extended beyond what is delimited as the frontiers of the five post-Soviet Central Asian states creating opportunities for new imaginations that are rooted in networks that operated across the region.

There is ample evidence of Indian merchants from different regions of the subcontinent moving well beyond the traditional boundaries of the South Asian subcontinent – the land frontiers traditionally marked by the Indus river in the west and Burma in the northeast. Indeed, it is worth recalling that large parts of Southeast Asia, Central and West Asia represented a region of economic and cultural influence facilitated by overland and oceanic trade routes that were well known and probably widely used several centuries earlier. In recent times various ‘New Silk Road’ Initiatives provide opportunities for exploring these multifaceted imaginations about the region. Within the metaphorical frame of the New Silk Road there were a number of strategies, most premised on prospects for overland connection between China, India, the Middle East, Europe and Russia resulting in revenue for the Central Asian states and sustainable development for Afghanistan. The American administration’s vision of Central and South Asia as a single interconnected region held together by Afghanistan is one such example.

Similarly, with the recognition of the fragility of connects in the immediate neighbourhood connections are now being sought with regions to India’s north and west that go back to antiquity and where there had traditionally been exchange of populations at different levels – as traders, scholars, and religious preachers. Politically many of these places are now no longer accessible to India, bringing to the forefront the necessity of connects with its immediate neighbourhood as a precursor to connectivity to a wider region. The ‘Connect Central Asia’ initiative has to be viewed within this context where both the traditional continental trade routes and the maritime multi modal routes would come into play. There also remains the alternative to connect Indian initiatives with other existing (like Turkey-Iran-Pakistan railway) or proposed routes (branches of the Silk Road Economic Belt). A multi modal link to Central Asia through the Iranian port of Chabahar could then link through existing and newer links to Russia and Europe. These include both transport corridors like the INSTC and pipeline projects like TAPI. The potential for both if linked to the South East Asian states would be manifold. Similarly the BCIM corridor could link to a broader Asian network.

The development of a network of Indian Ocean ports to serve as regional shipping hubs for littoral states with connecting highways and rail routes would mean leveraging India’s location in one of the most strategic stretches of ocean space. The launching of a Spice Route, Cotton Route and the Mausam Project, all of which are attempts to tie together countries around the Indian Ocean assumes significant in this context. At the macro level the aim of Project Mausam is to re-connect and re-establish communication between countries of the Indian Ocean world which would lead to enhanced understanding of cultural values and concerns while at the micro level the focus is on understanding national cultures in their regional maritime milieu. The aim is not just to examine connections that linked parts of the Indian Ocean littoral but also the connections of these coastal centers to their hinterlands. The ‘Spice Project’ aims to explore the multi-faceted Indo-Pacific Ocean World collating archeological and historical research to document the diversity of cultural, commercial and religious interactions in the Indian Ocean- extending from East Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, the Indian sub-continent and Sri Lanka to the Southeast Asian archipelago. The broader aim is to connect these with ‘Information Silk Route’ where telecom connectivity between the countries would be made possible. Partly propelled by the advancement in informational technology in India and partly by the fact that connectivity on the ground has been restricted by political reasons these strategies need to be visualized as integrated aspects of both domestic and foreign policy.

Reduced Indian presence in the Central Asian region today, means that there is generally an absence of reference to Indian communities in the region as a ‘significant’ diaspora in most enumerations. Indian communities in the US/UK and West Asia, who record substantial numbers, dominate the diaspora discourse leaving little space for what is identified as numerically ‘insignificant’ diasporas in the northwest closer home. Given the fact that the diasporas are today recognized as entities with significant soft power in the realm of foreign strategy this lack of engagement requires attention particularly since the political discourse is replete with references to reconnecting with the region. The need to reconfigure the economic geography of the region brings with it at least the necessity of bringing back into focus the diaspora communities that historically traded across the borders of what is now reframed as greater South Asia.

Anita

14 May 2017

To read more reflections, click here.