Asia’s Tryst with the Female Labour Force: Indices, Geopolitics, Revolutions, and Developments

Posted on : June 13, 2024Author : Annay De

At the time of the World wars, when nations were engaged in conflict and humanitarian crisis, an extraordinary transformation unfolded on the home front. As men were conscripted in droves, leaving vast gaps in the workforce, a call was sent out that would redefine the role of women in society. Seemingly overnight, women stepped into roles their fathers, brothers, and husbands had left behind. They donned helmets and overalls, taking up tools and machinery with a determination that would not only support the war effort but also challenge societal norms. The imagery was striking and revolutionary particularly in the United States; women operating turret lathes, assembling aircraft, and forging steel. During World War II, nearly 19 million women filled these critical positions. At LaGuardia airfield, for instance, forty women took over the maintenance of aircraft, including the iconic Boeing 314 Flying Boat, ensuring battle-readiness. The narrative was no less dramatic in factories and shipyards, where women like Vi Kirstine Vrooman (author of “A Mouthful of Rivets”) became riveters, and their work was symbolised and immortalised by the cultural icon “Rosie the Riveter”.

Although the “We Can Do It!” poster, by J. Howard Miller, was originally made as an inspirational image to boost worker morale, is often misinterpreted as “Rosie the Riveter”, the concept originated from a 1942 song by Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb, and was popularised through various media, including the government. This era marked a significant pivot in the story of women’s labour force participation, breaking barriers and laying the groundwork for future advances in gender and racial equality as African American, Hispanic, White, and coloured women worked side by side. It was a chapter of necessity and courage, where women not only proved they could fill the shoes left by men but also reshape their own destinies.

The Asian Female Labour Force Story

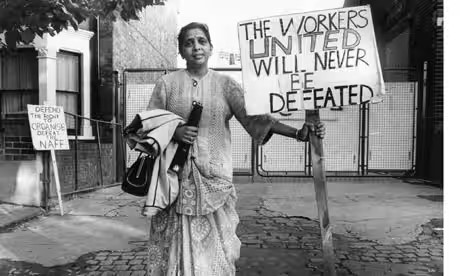

It was a time when women from around the world were fighting for their lives, rights, and livelihoods; especially in Asia, where history hasn’t been kind to women in the labour forces. In East Asia, the early 20th century saw a major shift as industrialization took hold. Japan and South Korea led the way, drawing women into factories to meet the demands of a rapidly growing industrial sector. These women, stepping away from traditional roles, faced harsh conditions, shunning (like the Korean female labourers who were called using their derogatory name “Gongsuni, a combination of the word common woman’s name (Gongdori) and factory (Gong Jang)), and low wages, and often ended up staging historic political protests such as the “New Factory Movement” or “Kongjang Saemaul Undong” of 1973 and the 1976 Naked Demonstration at Dong-il Textile Company. However, the change was happening, and it wasn’t going to stop. Over in China, the failure of the “Great Leap Forward” (1958-1962) brought about another wave of change, though not in the way the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) had planned. The unrealistic quotas set for industry and agriculture created chaos, leading to a significant labour shortage. Men were mobilised for industrial projects, leaving women to take over much of the agricultural work. This unexpected shift granted women more autonomy, compelling the CCP to create dining halls to feed the growing numbers of women working outside the home and to offer collective healthcare services. It was one of the first steps toward women in China gaining a foothold in the workforce and working toward the “Iron Rice Bowls”—stable, secure jobs that promised lifetime employment. Meanwhile, in South Asia, after countries like India gained independence in the mid-20th century, women started to enter the formal workforce. However, the majority of women were still confined to informal sectors like agriculture, where their work was often undervalued and underpaid. In Southeast Asia, the mid to late 20th century saw countries like Thailand and the Philippines experiencing a boost in female labour force participation. The rise of export-oriented industries, especially in garment manufacturing, created new job opportunities. Yet these jobs were often gruelling, with long hours, poor working conditions, and minimal benefits, reinforcing gender inequalities rather than addressing them. Central Asia, under Soviet rule, saw women being encouraged to join the workforce, yet the traditional social norms persisted, limiting real gender equality. And in West Asia, the situation was even more complex. While countries like Israel had relatively high female labour force participation rates, other countries maintained strict cultural and social barriers that severely restricted women’s participation in the workforce and their advancement within it.

Even today in the economic engine of Asia, a complex story unfolds regarding female labour force participation. While the region boasts impressive growth, significant disparities persist. Despite the glorified economic dynamism, female labour force participation (FLFP) presents a multifaceted picture. The World Bank reports a 2021 average FLFP rate of 53% in East and South Asia, lagging behind the global average (World Bank, 2022). This translates to a staggering 285 million fewer women contributing to the workforce. However, the landscape is far from uniform. Reports from a few Standouts like Vietnam (48.3%) and Armenia (52%) boast high participation, while others like Afghanistan (6.8%) and Pakistan (23.1%) face significant hurdles. This disparity reflects the interplay of educational attainment (ADB, 2016) – with higher female education correlating with higher FLFP – alongside cultural norms, health outcomes (WHO, 2023), and the dominance of informal work sectors, which often go unrecorded.

The Global Gender Gap Index (GGGI) by the WEF

The index scores and ranks countries based on gender gaps in economic participation, education, health, and political empowerment, and is an extremely important and relevant tool for understanding gender gaps. Asia demonstrates varied progress in terms of gender parity across its regions. In Eurasia and Central Asia, the gender gap stands at 69%, with leading countries like Moldova, Belarus, and Armenia, while Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, and Türkiye hold lower rankings. The region has shown incremental improvement since 2006, yet progress has stalled since 2020, suggesting that achieving full gender parity could take 167 years at the current pace. Economic Participation and Opportunity have seen a minor uptick, but Türkiye and Tajikistan still report less than 60% parity. Educational Attainment is high, with most countries exceeding 99% parity, though Türkiye and Ukraine fall short in secondary school enrolment. Health and Survival sits at 97.4% parity, but Azerbaijan and Armenia have concerningly low sex ratios at birth. Political Empowerment remains the most challenging area, with a score of just 10.9%, indicating significant underrepresentation of women in governance. In East Asia and the Pacific, the gender gap is similarly at 68.8%, placing it fifth among eight regions, but has seen stagnation over the past decade, with a slight decline in recent years. New Zealand, the Philippines, and Australia lead in gender parity, while Fiji, Myanmar, and Japan rank among the lowest. The Economic Participation and Opportunity sub index has declined, with nine out of 17 countries reporting fewer women in senior positions. Educational Attainment scores at 95.5%, with several countries achieving full parity, yet China, Lao PDR, and Indonesia lag behind. The Health and Survival subindex shows a dip to 94.9%, with a noticeable decline in sex ratio at birth across 11 of 19 countries. Political Empowerment, with a partial rebound to 14.1%, remains well below its 2018 level, with major countries like China and Japan regressing. Nonetheless, Australia and New Zealand have made notable strides in increasing women’s representation in government.

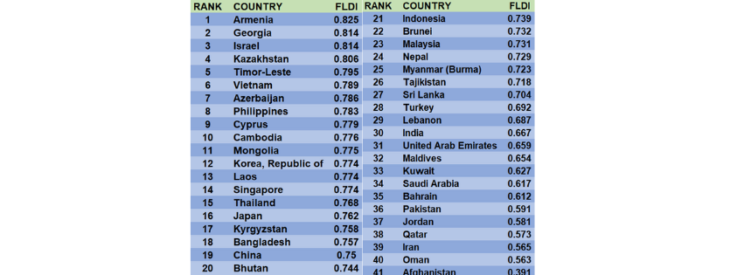

Constructing the Female Labour Development Index (FLDI) for Asia

With the GGGI as an inspiration, I’ve attempted to develop a Female Labour Development Index (FLDI). The FLDI attempts to score and consequently create an index and ranking for countries based on how well a nation augments the development of a strong female labour force. The judgement takes into account the countries’:

- Female labour force participation rate

- Educational attainment (includes male-to-female ratio of literacy rate, and enrolment in primary, secondary, and tertiary education)

- Health and survival (includes sex ratio at birth and healthy life expectancy

- Political empowerment (includes women in parliament, ministerial positions, years with female head of state and share of tenure years).

Values under each of these criteria are converted into scores and given weights. The highest weight being given to FLP rate, the second highest being educational attainment, thanks to the extremely significant correlation between the two, and lastly equal and third highest weights being assigned to health & survival and political empowerment. The 41 Asian countries have been ranked according to their scores (with the country with better development of female labour force being ranked higher) as follows:

Note: Due to the lack of data for some countries like Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Russia, complete coverage has not been possible.

Deciphering the Results

- Top Performers (FLDI > 0.8): Armenia, Georgia, Israel

The highest scores of these countries can be explained using their shared characteristics often associated with high female labour force participation (FLFP) such as their Soviet Legacy. The former Soviet Union emphasised female workforce participation, leaving a lasting impact on social norms and educational infrastructure. Their geopolitical situation as these countries face security concerns or regional instability, which can incentivize female labour participation as a necessity. (World Bank, 2023), and finally historical or cultural acceptance of women working outside the home could play a role.

- Mid-Ranking Countries (0.75 – 0.8): East and Southeast Asia such as Vietnam, Philippines, and Thailand

Explanatory factors may be rapid economic development which often creates new job opportunities, drawing women into the workforce (ADB, 2018), increased focus on girls’ education which can improve female skill sets and employability. (World Bank, 2022), and government policies like parental leave or childcare support which can ease the burden on working mothers (ILO, 2023). The Human Capital Theory can be used to explain that investments in female education (reflected in FLDI) often lead to higher female labour force participation and economic growth (Psacharopoulos, 1994).

- Lower-Ranked Countries (FLDI < 0.7): South Asia and the Middle East

The lower scores in these regions highlight persistent challenges such as the deeply entrenched patriarchal norms that can restrict women’s mobility and access to education, limiting their workforce participation, limited legal frameworks or protections for women in the workplace discouraging participation, and geopolitical instability as conflict and political unrest often disproportionately impact women’s opportunities. The Gender Convergence Theory which states that as economies develop, gender disparities in labour force participation tend to decrease (Galor & Weil, 1996) can be used to explain the scores of some Eastern and Southeastern Asian countries.

Epilogue

Female labour force participation represents a significant untapped resource. Reducing the gender gap is not just about equity—it’s a catalyst for economic expansion. For example, studies show that tackling gender discrimination in the workplace in the United States has played a key role in its recent economic growth (Hsieh et al., 2013). If these barriers were lifted globally, the potential economic gains would be substantial. Increasing female participation could boost productivity by 15-20%, with even greater impacts in developing economies. In Asia, removing gender bias could lead to a remarkable 30.6% increase in per capita income over a generation (Kim, Lee, and Shin, 2016b), yielding not only economic growth but also broader societal benefits. Empowering women in the workforce goes beyond economic gains; it drives social progress. Greater female labour force participation gives women more control over resources, leading to improved health outcomes for their children (Panda and Agarwal, 2005; Swaminathan, Lahoti, and Suchitra, 2012). Access to job opportunities also allows women to make more informed decisions about education and family planning, often delaying marriage and childbirth (Jensen, 2012).

However, higher female participation alone does not guarantee improved outcomes. The quality of employment is key. In some regions, such as Indonesia, unpaid family work may not lead to better welfare (World Bank, 2012; Berneiell and Sánchez Paramo, 2011). To realise the full potential of closing the gender gap, a multi-pronged approach is needed. This involves not just boosting participation rates but also ensuring job quality and addressing the burden of unpaid care work. By promoting decent work standards, investing in skills development, and dismantling barriers to women’s participation, we can achieve a truly inclusive and equitable economic development.

Hence, certain important considerations or problems which need to be addressed in terms of policy making endeavours are:

- Security Concerns: As seen in Armenia and Georgia, security threats can incentivize female labour participation to fill workforce gaps left by men engaged in military service or due to war casualties. This is particularly evident during wartime mobilisation efforts, but can also be a long-term consequence of living in a region with ongoing conflict.

- Resource Dependence: Oil-rich nations like those in the Persian Gulf often have lower female workforce participation due to a reliance on resource wealth. These countries can afford to import labour, often low-skilled male migrant workers, to fill many positions. Additionally, cultural norms surrounding female modesty and social roles can discourage women from working outside the home, even when economic opportunities exist.

- Political Transitions: Countries undergoing political transitions, especially those moving towards more democratic systems, can sometimes see a temporary rise in female labour force participation. This can be due to increased opportunities for political participation or a loosening of social restrictions on women’s mobility and employment. However, these gains can be fragile and may not be sustained in the long term.

- Regional Integration: Trade agreements and regional economic integration can create new job opportunities that attract women into the workforce. This is particularly true for jobs in export-oriented industries, such as garment manufacturing, which have traditionally employed a large share of female workers.

- Legal Frameworks for Migration: Countries with open policies towards female migration may see a rise in female labour force participation, particularly in low-skilled or service sectors.

- Social Safety Nets: The presence of strong social safety nets, such as unemployment benefits or subsidised child care, can make it easier for women to participate in the workforce, especially those who are single parents or have young children.

The journey towards gender parity in the workforce across Asia has been arduous and remains fraught with challenges, yet there is cautious optimism as progress, albeit uneven, continues to pave the way forward.

References

- Asian Development Bank (ADB). (2016). Gender Equality and Education in Asia and the Pacific. [https://www.adb.org/what-we-do/topics/gender](https://www.adb.org/what-we-do/topics/gender)

- Asian Development Bank (ADB). (2018). Reducing Gender Gaps in Labor Markets in Asia. [https://www.adb.org/news/new-adb-report-shows-improvements-women-economic-empowerment-gender-gaps-still-remain](https://www.adb.org/news/new-adb-report-shows-improvements-women-economic-empowerment-gender-gaps-still-remain)

- Berneiell, J., & Sánchez, R. (2011). Can Female-Headed Households Escape the Poverty Trap? ADB Briefs No. 71. Asian Development Bank.

- Galor, O., & Weil, D. N. (1996). Expanding the Model of the Family and the Labor Market: Theory and Evidence. American Economic Review, 86(1), 125-168.

- Hsieh, C., Hurst, E., Jones, M., & Klenow, P. J. (2013). Misallocation and the Gender Gap in Wages. Journal of the European Economic Association, 11(3), 427-462.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). (2023). Women and Work: Trends 2023. [https://www.ilo.org/publications/flagship-reports/world-employment-and-social-outlook-trends-2023](https://www.ilo.org/publications/flagship-reports/world-employment-and-social-outlook-trends-2023)

- Jensen, R. (2012). The Effects of Information and Cash Transfers on Gender Inequality: A Field Experiment in Ethiopia. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(2), 831-874.

- Kim, J., Lee, Y., & Shin, D. (2016a). Gender, Work, and Life Satisfaction in Korea. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(3), 1021-1042.

- Kim, J., Lee, Y., & Shin, D. (2016b). The Economic Consequences of Gender Bias in Korea. Feminist Economics, 22(3), 39-62.

- Panda, P., & Agarwal, B. (2005). Comparative Advantage in Uncertain Environments: Gender and Labor Market Outcomes in India. Journal of Development Economics, 76(1), 143-174.

- Psacharopoulos, G. (1994). Returns to Investment in Education: A Review of the Evidence. Education Economics, 3(1), 1-38.

- Swaminathan, H., Lahoti, G., & Suchitra, M. (2012). Women’s Empowerment and Child Health in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 47(18), 57-64.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2022). Women and Political Participation. [https://www.undp.org/publications/strengthening-womens-political-participation-snapshot-undp-supported-projects-across-globe](https://www.undp.org/publications/strengthening-womens-political-participation-snapshot-undp-supported-projects-across-globe)

- World Bank. (2012). World Development Report 2012: Gender Equality and Development. [https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/492221468136792185/main-report](https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/492221468136792185/main-report)

- World Bank. (2021). Women, Business and the Law 2021. [https://wbl.worldbank.org/](https://wbl.worldbank.org/)

- World Bank. (2022). World Development Report 2022: Finance for Equitable Development. [https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2022](https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2022)

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2023) Global Health Observatory data repository. [https://www.who.int/data](https://www.who.int/data)

Annay De

Intern, Asia in Global Affairs

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the text belong solely to the author, in his personal capacity. It does not reflect the policies and perspectives of Asia in Global Affairs.

Leave a Reply