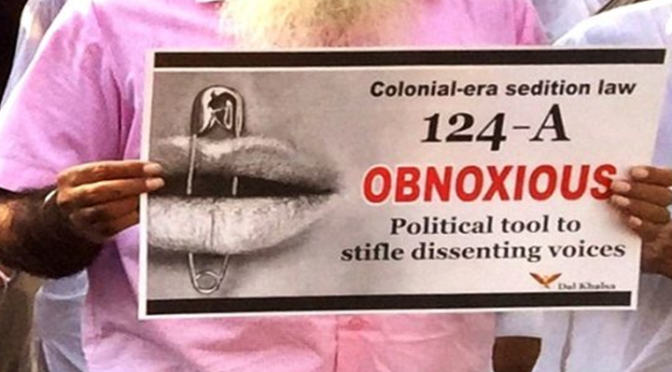

Sedition: An Anachronistic reminder of Colonialism

Posted on : February 16, 2019Author : AGA Admin

Freedom stands for the state of being free and the power of acting, in the character of a moral personality, according to the dictates of the will, without check, hindrance, or prohibition than such as may be imposed by just and necessary laws and the duties of social life. (Black’s Law Dictionary)

The freedom of a person under a democratic set up enables him to raise legitimate questions about the prevailing social order. However, this freedom is occasionally overshadowed by the enforcement of anachronistic colonial measures based on 19th century Victorian values which are obsolete in a democratic setup and are contradictory to the principles our Constitution.

The section which epitomises the discussion on the contradiction of the legal order is Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, 1860. The section is based on an act that came into existence in 1870 during the colonial rule as a measure to counter the ever increasing band of revolutionaries and as a systematic way of curbing dissent (then advocating for the end of imperial rule and establishment of an independent nation). But this section was never struck down and has always been a tool in the hands of the elected government of the day. This article focuses on why sedition is anachronistic and how it continues to be used as a systematic tool of oppression. It focuses on a number of cases in pre and post independent India with respect to the addressed section of the Indian Penal Code to trace the development and application of the section.

The sedition law came into existence as a part of the draft penal code suggested by Thomas Babington Macaulay in 1837. On further deliberation by Sir James Fitzjames Stephen it was included in the IPC to crack down on the mutinous activity of the revolutionaries. It heavily borrowed from the English treason law. But in practise while British treason law sought to punish directly disloyal feelings (evidenced by the fact that they are made public), sedition is intended not only to punish not one’s own disloyal feelings but causing (or attempting to cause) other people to have disloyal feelings towards the government. According to Sir James Stephen “the great peculiarity of the English law of treason was to regard every thought of the heart as a crime which was to be punished as soon as it was manifest by any overt act. (Donogh 1911).

In practice however, this distinction is a problematic one. Why would one incite disaffection if they did not themselves feel disaffection? How could a person truly harbour disloyal feeling towards the government and not have the desire to change the minds of others? So despite the careful wording, intended not to illegalise a person’s internal feelings, in practice what sedition does is make a “thought of the heart,” a crime. The law then proves to be a tool of thought control sanctioned by the government which leads to creation of an Orwellian state with the attributes of ‘thought policing’ enmeshed in it. This can have negative effects for the functioning of a democratic society because it directly attacks the basic ethos of democracy and does not allow people to articulate their views.

The purpose of sedition during British rule was to curb dissent and arrest revolutionaries for anti-imperialist activities. But the extent of anti-imperialist activities declined and the successive governments used this section to arrest dissenters. The literal interpretation of the section highlights that whoever through speech or action gives rise to anti-Government feelings will be arrested. But the context in which this section was drafted has lost its relevance today. And freedom of speech enables a person to hold a dissenting opinion (Arun Jaitley vs. State of UP).

However, freedom of speech is not an absolute right and restrictions to this have already been laid down in Article 19(2) in the Indian Constitution. (Saxena and Siddhartha Srivastava 2014). So at this juncture it is important for us to re-evaluate whether we need another section which labels people as seditious and creates the idea of false deviance. This remains important since Section 124A has attracted the attention of Judiciary in various judgements (Kedar Nath vs State of Bihar, Kanhaiya Kumar vs State of Nct Delhi,) and the rulings have held that this anachronistic section is still in prevalence.

What remains unanswered is whether every irresponsible exercise of right to free speech and expression can be termed seditious. Expression of frustration over the state of affairs, for instance, that does not threaten ‘the idea of a nation’ is not sedition. Interpretation by Courts have always been on the positive side and it has always emphasised that this section does not stand the Constitutionality Test. However, the apprehension always remains that this liberal interpretation might change and the section might be used to curb dissent. In light of this concern it is now time to begin a debate on the necessity of this section.

[124A. Sedition. —Whoever, by words, either spoken or written, or by signs, or by visible representation, or otherwise, brings or attempts to bring into hatred or contempt, or excites or attempts to excite disaffection towards, 102 [***] the Government established by law in 103 [India], [***] shall be punished with 104 [imprisonment for life], to which fine may be added, or with imprisonment which may extend to three years, to which fine may be added, or with fine. Explanation 1. —The expression “disaffection” includes disloyalty and all feelings of enmity. Explanation 2. —Comments expressing disapprobation of the measures of the Government with a view to obtain their alteration by lawful means, without exciting or attempting to excite hatred, contempt or disaffection, do not constitute an offence under this section. Explanation 3.—Comments expressing disapprobation of the administrative or other action of the Government without exciting or attempting to excite hatred, contempt or disaffection, do not constitute an offence under this section.]

Agniva Chakrabarti

The ideas expressed in the article belong to that of the author and do not reflect the position of Asia in Global Affairs

Leave a Reply