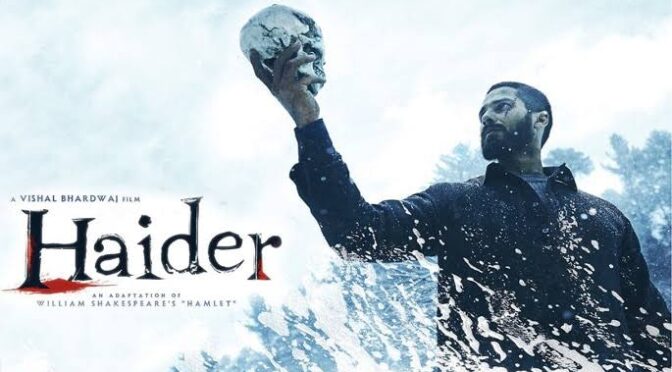

Haider (2014): Narratives of Loss, Identity, and Political Violence

Posted on : April 2, 2025Author : Adarsh Prasad

Directed by: Vishal Bhardwaj

Starring: Shahid Kapoor (Haider Meer), Tabu (Ghazala Meer), Kay Kay Menon (Khurram Meer), Irrfan Khan (Roohdar), Narendra Jha (Dr. Hilal Meer)

Vishal Bhardwaj’s Haider (2014) is more than just an adaptation of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, it is a dark, poignant, and politically charged cinematic masterpiece. Set against the backdrop of 1990s Kashmir, the film intricately weaves personal vengeance with the larger turmoil of insurgency and military repression. Bhardwaj masterfully reimagines Hamlet within India’s most politically sensitive region, delivering a narrative rich in compelling performances, evocative music, and a deep exploration of identity, loss, and resistance. The film’s portrayal of enforced disappearances, state repression, and insurgency transforms it into a crucial political text of our times. Echoing Shakespeare’s famous line, “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark,” Haider reminds us that something is equally rotten in the paradise called Kashmir.

The story follows Haider Meer (Shahid Kapoor), a young man who returns to his hometown after his father, Dr. Hilal Meer (Narendra Jha), a symbol of resistance, mysteriously disappears. As Haider uncovers secrets about his father’s fate, he is drawn into a web of betrayal and vengeance, mirroring Hamlet’s classic themes. His relationship with his mother, Ghazala (Tabu), grows more complex when he learns of her involvement with his uncle, Khurram (Kay Kay Menon), further fuelling his suspicions. A turning point comes when he meets Roohdar (Irrfan Khan), who informs him that Khurram orchestrated his father’s death under state custody. As Haider grapples with this revelation, his journey becomes a meditation on grief, justice, and the cyclical nature of violence.

Haider’s internal struggle resonates through the film’s reimagining of Hamlet’s famous soliloquy: “To be or not to be” becomes “Hum hain ki hum nahin?”, reflecting the broader identity crisis of Kashmiris. Bhardwaj, along with co-writer Basharat Peer, crafts a taut screenplay that seamlessly blends personal tragedy with political unrest. Pankaj Kumar’s cinematography beautifully captures Kashmir’s stark beauty, where snow-clad landscapes and misty valleys contrast with the ever-present spectre of violence, underscoring the region’s relentless struggle for justice.

Shahid Kapoor delivers an almost flawless performance, rich in subtle nuances, raw intensity, and a remarkably deep portrayal of Haider, capturing his descent from grief to rage with depth and complexity. His transformation, from a vulnerable son to a man consumed by revenge, is both unsettling and profound. Tabu’s portrayal of Ghazala is equally mesmerising, capturing the intricacies of a mother torn between love, survival, and political realities. Kay Kay Menon’s Khurram exudes chilling manipulation, adding layers of psychological intrigue. Every frame brims with symbolism, the desolate beauty of Kashmir juxtaposed against political brutality serves as a constant reminder of the land’s turbulent history.

Bhardwaj’s use of Kashmiri poetry and traditional elements, such as Pheran-clad gravediggers singing “Aao Na,” heightens the film’s haunting atmosphere. The music, particularly “Bismil,” vividly portrays Haider’s transformation, blending Kashmiri folk with a political allegory. The score, infused with traditional Kashmiri melodies, further elevates the narrative’s emotional depth.

Haider is unflinching in its political commentary. While it does not explicitly endorse any ideology, it exposes the brutal realities of the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA), extrajudicial killings, and enforced disappearances that marked Kashmir’s insurgency-ridden period. From a postcolonial perspective, Haider examines subaltern resistance against hegemonic state power, drawing from the theories of Giorgio Agamben and Michel Foucault. Agamben’s concept of the state of exception, where legal norms are suspended to maintain sovereignty, resonates deeply in the film’s depiction of AFSPA’s unchecked power. The film critiques how counterinsurgency operations blur lines between justice and oppression, highlighting the erosion of civil liberties and the cost of political agendas.

One of the film’s most striking aspects is its critique of the radicalisation of youth amid systemic injustice. Haider’s descent into violence mirrors the disillusionment of many young Kashmiris caught in a relentless cycle of repression and rebellion. The film does not romanticise violence but rather presents it as a tragic consequence of a system that fails to deliver justice.

In today’s world, where populist politics, state-sanctioned violence, and misinformation dominate, Haider remains deeply relevant. Its portrayal of a conflicted state apparatus, where personal vendettas are masked as patriotic duty, resonates beyond Kashmir, echoing struggles in regions like Palestine, Xinjiang, and post-9/11 detentions. The film urges viewers to question power structures and recognise recurring patterns of state overreach.

A decade after its release, Haider continues to hold significance, particularly in the wake of the revocation of Article 370 in August 2019, which stripped Jammu and Kashmir of its special status. The film’s themes of alienation, fear, and identity crises remain relevant as many Kashmiris feel increasingly marginalised. Haider is not just a cinematic triumph but a searing critique of political oppression, resonating with struggles for justice worldwide. In a world where identities are shaped and suppressed by political forces, Haider’s existential question, “Hum hain ki hum nahin?”, remains as haunting as ever. Cinema, particularly in contested spaces, does not merely tell a story, it reflects the prevailing ethos of its setting, with its lens moulded by the socio-political realities of the land it depicts.

Adarsh Prasad

M.A. Political Science

St. Xavier’s College (Autonomous), Kolkata

Intern, Asia in Global Affairs

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this film review are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Asia in Global Affairs. The review is intended for academic and informational purposes only. It is not an endorsement of any particular viewpoint, nor is it intended to malign any individual, group, organization, company, or government.

Leave a Reply