Deal or No (Green) Deal Does the Union Budget 2022 arrogate its commitment to mitigating climate change?

Posted on : March 12, 2022Author : Ayanika Das

In this article, we analyse the Union Budgets’ failures and successes in incorporating climate change as an important point of focus. The present government has made pledges at the Paris Conference and COP26 summit, and while the finance minister has made a move towards the renewable energy sector and reducing carbon output, it stands at odds with the proposals for infrastructural development. This stance of abating climate change with promises is not a new discourse, but given how we as a planet stand at the crossroads of “clear and present danger”, we must give the matter the attention it needs. Whatever be the victories of the Union Budget, it makes the cardinal error of choosing development over global warming, the price of which is bound to be heftier and more catastrophic.

Union Budget 2022, Finance, Climate Change, Green Deal, COP26, Global Warming, Panchamrit.

The ‘Union Budget’ delimits the diversified expenses and liabilities of the administration. It is the most extensive fiscal document for any country. Historically, there has consistently been a substantial divergence between combining our duty towards the environment with the obligations of overseeing the development and infrastructural growth. Specifically, a post-colonial state like India, with its implicit social fault-lines, economic backwardness and security concerns, has been pursuing strategies concomitant to production and development but detrimental to the climate. The total allocation for the five autonomous bodies under the Union Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) — GB Pant Himalayan Institute of Environment and Development, Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education, Indian Institute of Forest Management, Indian Plywood Industry Research Institute and Training Institute and Wildlife Institute of India — is Rs 287.45 crore, which is less than last year’s budget by Rs 18.05 crore.

In this light, it is vital to identify how the commitment of an advancing country to engaging in a green deal displays a Catch-22 situation: insufficient focus on climate change initiatives implies unfettered infrastructural development and resource use which further solidifies the need to make, said climate pledges. After all, long gone are the days when Mrs Indira Gandhi could champion the exclusion of the third world nations, limited in their capacity to make proactive, systemic policies, to pay their share of the cost of Global Warming. Now, India boldly proclaims its zeal towards fulfilling its “fair share of responsibilities”, matching the Global North in walking the talk.”

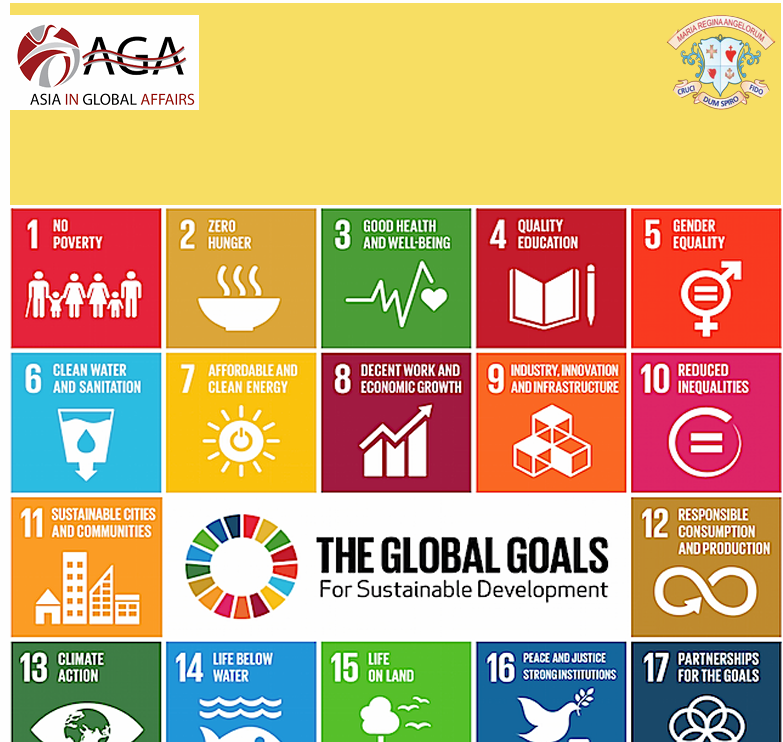

In the 26th session of the Conference of the Parties (CoP26) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), Glasgow, PM Modi delivered a statement bolstering his administration’s concerted efforts to fulfilling what he designated the Panchamrit’, whereby the country will:

- bring its non-fossil energy capacity to 500 GW by 2030.

- bring its economy’s carbon intensity down to 45 per cent by 2030.

- fulfil 50 per cent of its energy requirement through renewable energy by 2030.

- reduce one billion tonnes of carbon emissions from the total projected emissions by 2030.

- achieve Net Zero by 2070.

Therefore, by these accounts, India looks to serve as an eager partner in global efforts to find a sustainable green deal. However, the gap in theory and practice is already clear in the National Budget presented on the 1st of February 2022.

It is a given that any fiscal account will emphasize some sectors more pressingly than others, but the searing lack of climate policy initiatives suggests how it evades being seen as a potent area of concern, nationally at least. No single ministry fulfils the goal of net-zero as the ministries of new and renewable energy (MNRE), environment, forest and climate change (MoEFCC), and heavy industries are combinedly tasked with seeing through India’s efforts in this direction. It was expected that to fulfil renewable energy standards, budgetary allocations would be made to fund such schemes. However, the coal ministry received a larger share of budgetary allocation, as opposed to the MNRE or MoEFCC. India is the world’s third-largest carbon emitter, despite a low per capita record. To achieve the grandiose vision of carbon neutrality, also known as net-zero greenhouse gas emissions, by 2070, India needs investment support of $1.4 trillion [Rs 105 lakh crore],” according to an analysis by Delhi-based think-tank Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW). Yet budgetary shares are repeatedly denied to the environment and renewable energy ministries, in favour of coal, which is coincidentally the biggest source of carbon emission. We simply cannot expect to cut our cake and have it too.

Finance Minister, Mrs Sitharaman described climate change as the “greatest external risk for the Indian economy” but the budgetary push for high emission, high energy infrastructure, makes her sentiment a tad farcical. The ‘Gati Shakti’ scheme plans to foster growth through facilitating capital expenditure in areas such as roads, railways, airports, etc. There is mention of clean energy in the program’s description, and some of the policy proposals, such as investment in high-efficiency trains, may help achieve these plans. But the fiscal allocations remain poorly distributed, as while the Environment sector has registered a ₹3030 crore investment, the Transport sector has seen a 68% increase in investment to ₹2lakh while the demarcated civil aviation budget is a whopping ₹10677 crores. Aviation, is by every account, the highest emission-intensive sector. While an emphasis on lower cost, relatively faster transport is the need of the hour, the focus on achieving it remains minuscule as opposed to the proposed high pollution and emission causing infrastructural proposals. ‘Gati Shakti’ has to balance stimulating the economy while empowering low-carbon and climate-resilient development.

The most damning pitfall of the budget is its lack of attention towards mitigating air pollution. While the allocation for the ‘Commission on Air Quality Management’ has decreased slightly, the allocation for the ‘National Clean Air Programme’ remains minimal. India has committed to long-term goals of air quality improvements and to fulfil those objectives, there is an urgent need for greater investment in monitoring and enforcement capacity.

The budget further risks undercutting one of India’s successes in the fight against air pollution – the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY) scheme, which engenders rapid expansion of LPG usage to women of BPL families. The budget estimate for the PMUY for 2022-23 is Rs 4,000 crores, falling sharply from Rs 12,000 crore in 2021-22, and over Rs 26,000 crore in 2020-21. This is because it discontinued LPG subsidies through the Direct Benefit Transfer scheme in May 2020 due to low global oil prices. Since then, domestic LPG prices have increased by over Rs 300 per cylinder. This price rise, coupled with the COVID hit economy, means that domestic LPG is effectively unaffordable to most PMUY beneficiaries. To solidify the gains made in the last several years, we should reinstate pronto these subsidies. Experts further note that the erasure of PMUY from the budgetary discourse is concerning as household cookstove smoke is a large source of air pollution nationwide, and contributes to several deaths annually, primarily among women and young children.

The Budget is not entirely suspect in its climate abating tendencies and to portray it as completely incompetent is also a false narrative. On the positive side, the government will now focus on promoting chemical-free natural farming solutions, collaborating with farmers’ lands close to river Ganga, said Sitharaman. The Jal Jeevan Mission has a revised estimate of Rs 60,000 crore for the fiscal year 2022-23, as does the ‘The National Mission for Green India’ and Project. Another notable move to help the transition to a carbon-neutral economy is the plan to co-fire 5-7% biomass pellets in thermal power plants, resulting in CO2 savings of 38 MMT annually. This will help avoid stubble burning in agriculture fields while “providing job opportunities and extra income to farmers”, noted Sitharaman. There is a substantial push for electric vehicles as well, with the government planning to bring in a battery-swapping policy. Battery-swapping is exchanging a discharged electric car battery for one that is already charged. The concept of “Sovereign Green Bonds” has been introduced. Any sovereign entity, inter-governmental group, or corporation can issue these bonds to utilise the proceeds of the bonds for projects classified as environmentally sustainable. . In urban areas, ambitious special mobility zones with zero fossil-fuel policy are said to be promoted. Additionally, the Budget Session expects to discuss ‘The Energy Conservation (Amendment) Bill, 2022,’ which aims “to provide regulatory framework for Carbon Trading in India while adhering to an effective implementation and enforcement of the Energy Conservation Act, 2001.

How India can commit to action internationally, without a full-proof plan of action domestically, is perhaps the biggest indicator of this government’s credentials as a true vanguard of change, albeit on paper. The goal years of 2070 and 2030 may seem too distant into the future to consider, but a barrage of scientific, peer-reviewed reports from the ‘Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’ and ‘Breakthrough National Centre for Climate Restoration’ to name a distinguished few, repeatedly forewarn that we as a civilization have till approximately 2050 to abate global warming. Post that timestamp, we may face conditions that can only be described as straight out of the sets of ‘Mad-Max’. The government has to furnish policies that help meet target emission rates while proliferating development and progress.

Ayanika Das

Intern, AGA

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the text belong solely to the author, in her personal capacity. It does not reflect the policies and perspectives of Asia in Global Affairs.

Leave a Reply