Book Review: Strangers Of The Mist: Tales Of War And Peace From India’s Northeast.

Posted on : August 22, 2022Author : Upoma Ganguly

Title: Strangers of The Mist: Tales of War and Peace from India’s Northeast

Author: Sanjoy Hazarika

Published by: Penguin India.

Date: 2000 (originally published in 1994)

Length: 408 pages; Price: Rs. 320.

Abstract: Strangers of The Mist: Tales of War And Peace From India’s Northeast is an insightful and path-breaking account of India’s North-Eastern states or the “7 sister states” with specific focus on the issues and insurgencies of Assam, Nagaland, Manipur and Mizoram and the role India’s neighbours played in shaping the political landscape of the region. Hazarika’s book follows the inception of the “northeast” as we know it today along with the political, linguistic, and cultural divisions, fierce revolts, brutal suppressions and ruthless bloodshed that have marred the region.

Keywords: North-Eastern states, India’s North-East, Assam, Nagaland, Bangladesh, New Delhi, insurgency, CAA, NRC, AFSPA, Manipur, Mizoram.

Veteran journalist and activist Sanjoy Hazarika is one of the most prominent voices from the North-East, who is a native of Shillong himself, and one can feel the deep affection and admiration he holds for his own hometown, along with a sense of solidarity with the people of North-East and their struggle, as it bleeds through his evocative writing.

The opening segment of the book features an exchange the author had with a village elder at the Thankip village of Arunachal Pradesh who said their traditions have been destroyed and soon they would become “nowhere people” and rhetorically asked where they are headed. This question encapsulates the book quite well – the author has provided meticulous details and thorough backgrounds in each of the issues he presents before the readers in separate chapters, both in the context of grassroot changes and geopolitical implications, in an attempt to understand what the future holds for the region without trying to predict an answer in such unpredictable terrains.

When Sanjoy Hazarika’s epic tale following the tumultuous position of India’s Northeast and its people was published, there still weren’t many significant pieces of literature on the region and it was heralded by many as shedding light on a region that was till-then shrouded in mist.

Through his immersive writing, Hazarika slowly bares the crux of the decades-old conflicts of the North-East – alienation from the mainland that is felt by a oft-overlooked yet diverse demographic of people living in the scenic Lushai hills, Naga hills and on the banks of the flood-prone Brahmaputra.

This feeling of alienation is justified as there is hardly any mainstream representation of the people living in these states and the issues faced by them or their cultures barring absurd, negative stereotypes. The Indian Union Government instead keeps pushing for an unified India whilst simultaneously disrespecting the indigenous languages and cultures of the hill tribes. Further alienation is a product of the lack of awareness amongst the average Indians regarding the North-Eastern states which often culminates into malicious attitudes and racism towards those hailing from there.

Although the book was first published in 1994, it remains eerily accurate even for the present scenario, which begs the question – has the Indian administration’s stance remained so stagnant on such a glaring issue for so long?

The first segment of the book largely deals with the issue of immigration and assertion of culture in Assam.

The continuous influx of Bangladeshi immigrants to the border state of Assam remains to be one of the most intractable issues faced by independent India – one that has permanently changed the status-quo of the state. The Assamese political lobby has long expressed their deep dissatisfaction with the Bengali immigrants that continue to dominate the social and political sphere at the cost of the former’s own culture being side-lined – the Assamese language received recognition as an official state language in only 1960, before which Bengali and English were considered as the lingua franca of the land.

The author notes that the lax borders between Assam and Bangladesh have been a haven for illegal activities including drug smuggling, illegal immigration, and many other offences.

Hazarika notes that while the partition of India and the freedom movement of Bangladesh have both been catalysts that set off a course for migrants to journey through the lowlands of East Pakistan (modern Bangladesh) in order to escape the war and poverty to the promise of safety and security in India, the seeds of the demographic problem faced by Assam were planted in the pre-independence period itself. In a tussle of power between the Indian National Congress, the British colonial administration, and the Muslim League – Assam’s politically landscape went through many changes to accommodate the vision of whichever party was in power.

The calls of independence still echo in the hills today. Exerting the right to self-determination and formation of a separate state have been one of the most crucial demands made by many hill communities. Hazarika focuses on all the major uprisings that the hills have witnessed.

The cause of the Naga independence and the bloody aftermath of the resistance that remains to be of the most brutal military crackdowns in the country yet garners very little attention from mainstream media and political discourse.

The Mizo uprising in Lushai Hills and the the Meitei uprising of Manipur also are significant in resisting the big-brotherly attitude of a central government that remains aloof to the concerns of the natives of the region and continues to only take notice of any issue only when an active rebellion breaks out making clashing between the two sides inevitable.

The author does not shy away from criticizing New Delhi’s ad-hoc policies in the North-East which aims for surface level solution and remains patronizing instead of trying to learn more about the unique culture of the different communities and tribes of the North-East. He expresses his frustrations over the central administration’s repeated failures quite clearly, in his own words – “Over the past decades, India’s policymakers have failed to develop an evolving, forward-looking security doctrine that covers the umbrella of national and international geo-political concerns.” And despite the years that followed the publication of Hazarika’s book, one cannot be certain that the mist surrounding the North-East of India has lifted.

The implementation of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) in Assam along with its twin policy of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in 2019 has been a process plagued with mismanagement and corruption which was flawed from the very beginning. It has rendered countless stateless.

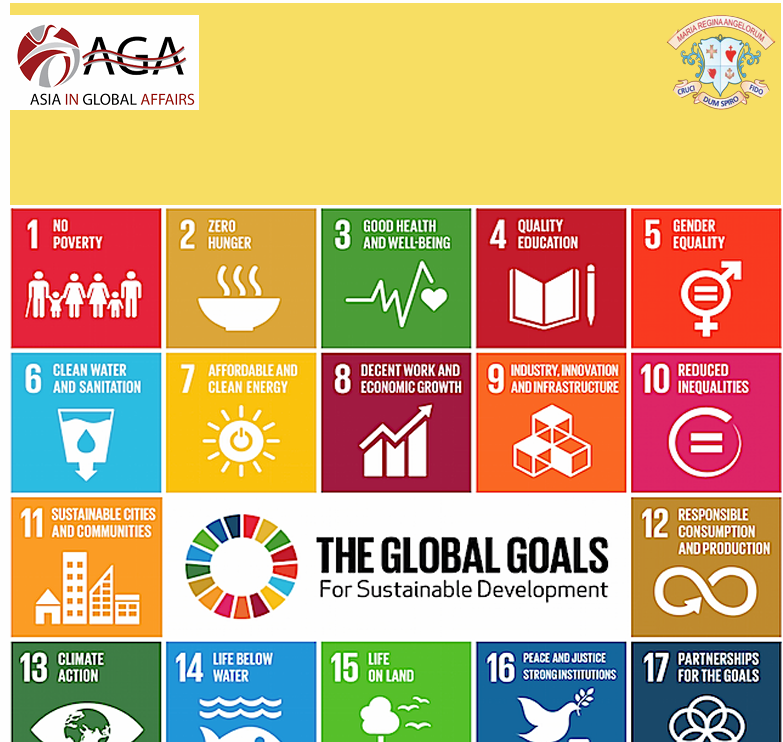

Representation is a powerful way for marginalized communities to take charge of their own narrative which is still unfortunately mostly absent with regards to the mainland’s attitude towards the seven sister states.

There is a dearth of reportage on the North-East of India in the mainstream media. The devastating floods that wreaked havoc on the state of Assam a mere month ago was severely under-reported by the popular media channels showing a stark disparity between the treatment received by the North-Eastern states and the mainland.

However, there have been significant improvements regarding the position of the North-East in both academia and culture – Hazarika’s pioneering work has inspired and influenced many academics, authors, filmmakers, and storytellers to share their own experiences and culture re-contextualizing the significance of the region in the modern day.

The North-East is a centre of connectivity between India and its eastern neighbours including Myanmar and the importance of the region in the context of foreign relations should be emphasized now more than ever in the light of “Look East” policy aiming to cultivate extensive economic and strategic relations with the nations of Southeast Asia and countercheck China’s growing influence in the region.

Upoma Ganguly

Intern, Asia in Global Affairs

Reference:

Hazarika, S. (2000). Strangers Of the Mist: Tales of War And Peace From India’s Northeast. Penguin India.

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the text belong solely to the author, in her personal capacity. It does not reflect the policies and perspectives of Asia in Global Affairs.

Leave a Reply