Secularism in Bangladesh: A Paradox

Posted on : May 30, 2024Author : Debendra Sanyal

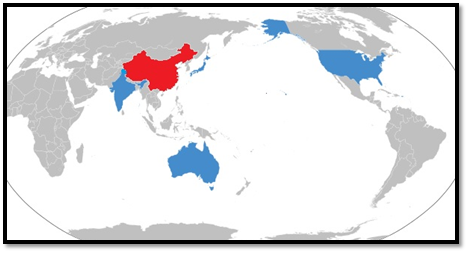

Article 2A of the Constitution of Bangladesh says that Islam is the state religion of the country, but will also ensure equal status and equal right in the practice of other religions, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, and Christianity. Also, Article 12 of the same Constitution declares that Bangladesh is a secular country, and the Constitution counts secularism as among the Fundamental Principles of State Policy. We can see that two contrasting positions are operating at the same time, a country having an official state religion, yet declaring itself as secular. However, complexity is something that is synonymous with Bangladesh, and it has been more or less the same case with regards to secularism in the country. Recent political trends in the country suggest that the national political parties are kowtowing to Islamist fundamentalist groups in order to either come to power or stay in power. In theory, the state is secular, but in practice, the line between religion and the state has been considerably blurred. In this paper, we will look at how secularism has panned out in Bangladesh.

Secularism, and its sowing in Bangladesh

Secularism essentially refers to the state dissociating itself from religion and not interfering in the religious matters of citizens. The concept took shape in Europe during the modern period, when the newly-emerging nation-states were trying to break free from the control of the Church. The Western model of secularism involved “a separation between ‘the secular,’ which is state, economy, science, art, entertainment, health and welfare, and ‘the religious,’ which are ecclesiastical institutions and churches.” (Wohab, 2021) Through the 19th and 20th centuries, secularism got exported to the rest of the world, but it had to adapt with the local conditions. In the South Asian context, the Western version of strict separation between religion and the state was not feasible, hence secularism had to be remodelled, wherein it was not based on a “strict wall of separation,” rather on a principle of distance between religion and state. (Bhargava, 2011, as cited Wohab, 2021)

Bangladesh became independent in 1971, following the Liberation War, wherein it separated from Pakistan. As erstwhile East Pakistan, the region had a substantial Hindu minority population, as well as other religions, while Pakistan as a whole was an Islamic Republic, with no real provision for secularism. The political establishment in West Pakistan viewed the eastern wing with suspicion and distrust for many reasons, one of them being the considerable non-Muslim population there, and treated them as second-class citizens. Prior to the 1971 War, the Pakistani Army committed genocide on the people of East Pakistan, particularly the minorities, in order to quell the secessionist movement. After independence, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the founding father of Bangladesh, decided that secularism would be one of the fundamental pillars of the nation-state. This decision was made based on the Pakistan experience and the horrors of the genocide. Thus, secularism became enshrined in the 1972 Constitution, and Islamic-based political parties were banned due to their pro-Pakistan leanings. There are also arguments about external imposition of secularism on Bangladesh. “According to this argument, political pressure, especially from India due to its support for Bangladesh during the liberation war, played an important role in determining Bangladesh’s secular identity.” (Mostofa, 2021) The model of secularism in Bangladesh is similar to that of India, which is that the state maintains a principled distance from all religions and views all religions as equal. “Bangladeshi secularism translates into Dharmanirapekkhata (religious neutrality). The Bangladeshi state does not disassociate itself from religion; rather it accepts the role of religion in public spheres. And in the eyes of the state all religions are equal.” (Mostofa, 2021) During his tenure as Prime Minister, and later President, Sheikh Mujib allowed the broadcasting of verses from the holy texts of the country’s four main religions over national television and radio.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the founding father of Bangladesh

The Islamist turns during military rule and beyond

After the assassination of Sheikh Mujib in 1975 and the subsequent military coup, secularism took a major hit in Bangladesh. Taking a leaf out of the book of General Zia-ul-Haq of Pakistan, the military regimes of Major-General Ziaur Rahman and General Hussein Muhammad Ershad resorted to Islamic appeals in order to legitimise their rule. Zia removed secularism from the Constitution in 1977, and replaced it with ‘Absolute Trust and Faith in the Almighty Allah,’ along with revoking the ban on religious parties. “The military regime succeeded in bringing Islam into political discourse and public life, facilitating the legitimacy of the Islamists both constitutionally and politically… The state-controlled media began to broadcast Islamic programmes and devoted more time to religious issues.” (Wohab 2021) The Islamisation trend continued further under General Ershad, who made Islam the state religion in 1988. Ershad’s promotion of the Islamisation process was a “naked political ploy to use Islam as a policy of statecraft (which was) to gain more friends and allies among Islamic countries as well as to legitimise his autocratic rule.” (Guhathakurta, 2012) During the period of military rule, the Jamaat-e-Islami, who had notoriously supported the Pakistani Army during the 1971 War, became the prominent Islamist political party.

Democracy returned to Bangladesh in the 1990s, but the two leading parties of Bangladesh, the Awami League led by Sheikh Hasina, the daughter of Sheikh Mujib, and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party led by Khaleda Zia, the wife of Major-General Ziaur Rahman, continued to appease the Islamist parties and groups, particularly the Jamaat-e-Islami. The parties wanted the support of the Islamists “either to gain power or to remove a democratically elected regime. Both parties became successful in gaining support from JI when they needed to form a government or organise a political movement.” (Wohab, 2021) The influence of Islamists in the government led to national policy being a reflection of their interests, as evidenced by the proliferation of madrasas and growth of Islamist organisations. The trend continued into the 21st century as well, and the role of Islamist parties as kingmakers got further entrenched, with many fundamentalist leaders becoming cabinet ministers.

Major-General Ziaur Rahman, former military ruler of Bangladesh

The secularist-Islamist dynamic

In 2009, the Awami League under Sheikh Hasina came to power, with one of its electoral campaign promises being the restoration of the secularism provision in the Constitution. Two years later, secularism was back in the Constitution, but Islam continued to remain the state religion of Bangladesh. This became symptomatic of a new trend: theoretically the state is secular, but the government would continue to pander to the Islamist demands. Many recent incidents point towards this trend. In 2013, the Shahbagh Movement took place, in which people demanded death penalty for the 1971 Liberation War criminals, many of them belonging to Islamist organisations. In response, the Islamists, led by Hefazat-e-Islam, launched a counter-movement against Shahbagh, branding the participants of the Shahbagh Movement as atheists and accusing them of blasphemy. The Awami League government kept vacillating between the two, and had caved into the demands of Hefazat by withdrawing their support to the Shahbagh Movement. In 2017, the government made changes to the school curriculum by removing chapters written by secular and atheist writers such as Humayun Azad and Rabindranath Tagore, and replacing them with overtly religious lessons, under pressure from Islamic fundamentalists like Hefazat. At the same time, the government banned a number of radical Islamist organisations who were involved in terrorist attacks across the country, such as the Hizb-ut-Tahrir and Ansarullah Bangla. However, religious minorities continue to feel threatened in Bangladesh due to the emboldened Islamist groups. According to the human rights group Odhikar, “Between 2007 and 2019, 12 people belonging to minority faith communities were killed, 1,536 injured, seven abducted and 19 raped, while 62 pieces of land and 40 houses were grabbed, 1,013 properties and 390 temples were attacked, and 889 idols damaged or destroyed.” (Ahmad, 2020) Coming to freedom of expression on religious matters, the stance of the government is once again ambiguous. “For instance, a number of official statements on the recent murders of online activists were ambiguous. While condemning the threats and acts of violence, Government representatives also admonished individuals expressing critical views on religion, asking them not to go ‘too far’ in their criticisms.” (Bielefeldt, 2015, as cited in Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2015) Hence, we can see here that the state is trying to keep up a secular façade, while also ensuring that they do not lose out on the support of the Islamists, for they constitute an important source of political support. A paradoxical dynamic is at play here.

Members of the Hefazat-e-Islam, a religious fundamentalist organisation in Bangladesh

Conclusion

In conclusion, Bangladesh started out with the intent of not repeating the same experience which it faced when it was a part of Pakistan. The constitution makers enshrined secularism as one of the fundamental pillars of the state. However, after the assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the military regime moved away from the secular premise, and explicitly resorted to Islamisation in order to legitimise their rule. This unleashed the religious fundamentalist forces into the body politic of Bangladesh, whose effects can be felt to the present day. Secularism effectively got removed from the Constitution of Bangladesh. After the return of democracy, the leading national parties of Bangladesh continued to seek the support of Islamist parties like the Jamaat-e-Islami, and these parties went on to become kingmakers. They also influenced national policy, as governmental initiatives often reflected their interests. In the present century, even though the Hasina government restored secularism in the constitution in 2011, Islam continued to remain the state religion of Bangladesh. This created a contradictory situation, wherein the state was committed to secularism on paper, but in reality, continued to appease Islamist interests. This has reflected in incidents such as the Shahbagh Movement and the revision of school curriculum in 2017. Moreover, this ambiguity has affected the condition of religious minorities, as they have been subjected to numerous human rights abuses by the Islamist organisations. Therefore, secularism in Bangladesh today is stuck in a paradox.

___________________________________________________________________________

References

Ahmad, A. (2020, December 16). Secularism in Bangladesh: The troubled biography of a constitutional pillar. The Daily Star. https://www.thedailystar.net/supplements/news/secularism-bangladesh-the-troubled-biography-constitutional-pillar-2011933

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2015, September 9). Bangladesh: a secular State with a State religion? https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2015/09/bangladesh-secular-state-state-religion

Guhathakurta, M. (2012). Amidst the winds of change: the Hindu minority in Bangladesh. South Asian History and Culture, 3(2), 288-301. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/19472498.2012.664434

Mostofa, S. M. (2021, December 6). Bangladesh’s Identity Crisis: To Be or Not to Be Secular. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2021/12/bangladeshs-identity-crisis-to-be-or-not-to-be-secular/

Wohab, A. (2021). “Secularism” or “no-secularism”? A complex case of Bangladesh. Cogent Social Sciences, 7, 1-21. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/23311886.2021.1928979?needAccess=true

___________________________________________________________________________

Debendra Sanyal

Intern, Asia in Global Affairs

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the text belong solely to the author, in his personal capacity. It does not reflect the policies and perspectives of Asia in Global Affairs.