Invisible Frontlines: Women’s Varied Role in War

Posted on : September 15, 2024Author : Mahek Daima

When war breaks out the world’s attention turns to the men on the front lines. But what about the unseen women who remain behind, taking on multiple roles to ensure their families and communities survive? Where are these women? In traditional historical accounts of war, women’s roles are often invisible This paper explores the often-overlooked roles and experiences of women in war-torn regions, which challenges the conventional expectations. According to UN ,nearly eighty percent of the displaced population constitutes women and children facing threats of violence, exploitation, and severe scarcity of resources. These atrocities are not just statistics; they are stories of mothers, daughters, and sisters whose bodies have become battlegrounds in a war they did not choose. While traditional war accounts focus on the masculine narrative, this paper seeks to answer, “Where are the women in war?” by exploring the challenges faced by women in war-torn regions and their extraordinary contributions amidst brutality. This article uncovers the voices of women subjected to extreme wartime conditions. Through case studies of war zones in Asia, it investigates systemic sexual violence, exploitation, and societal marginalization endured by women in Japan, Afghanistan, and Cambodia, highlighting that war is a gendered phenomenon. Ultimately, this study advocates for reevaluating gender relations during and after conflicts, recognizing women not just as victims but survivors of the war and crucial agents of peace and rebuilding in the post conflict conditions.

Japan More than sixty years since World War II ended, yet the wounds of Japanese colonialism still fester in East and Southeast Asia. A tragic consequence for women in war zones is sexual violence, exemplified by the “comfort women” of WWII. During the war, Japan sought to improve troop performance by establishing government-mandated prostitution, hoping to reduce rapes and civilian killings. Few women volunteered, leading to the informal “selling” of daughters, kidnapping, and trafficking of women and girls. This paper explores their harrowing experiences, disclosing the impact of such brutal policies.

Comfort women in Japan

Women from Korea, China, the Philippines, and Japan were forcibly held in military brothels during WWII, facing systematic rape, physical abuse, and psychological torment. Many were deceived with false promises of employment or coerced through violence. Chinese and Korean women were particularly targeted, and Japanese women, being fewer in number, were considered more costly. After the war, to prevent sexual violence from American soldiers, the Japanese government set up the Recreation and Amusement Association. They recruited poor Japanese women promising food and shelter but later, they resorted to intimidation and coercion tactics.

Despite the closure of the association, rape cases increased under Allied occupation. Yi Sun-ok, a Korean comfort women’s survival story describes how a young girl’s desire and aspiration to become an independent “new woman” was shattered when her neighbor, Mr. O delivered her to a military brothel in Guangdong, southern China. The dichotomy of being celebrated as national heroes while engaging in such inhumane acts of sexual violence uncovers the complex and brutal nature of war towards women.

Afghanistan

Gender isn’t binary, it is a hierarchy. And In the last two and a half years after regaining power in Afghanistan, the first thing that the Taliban did was restore those very oppressive practices that robbed women of their rights, happiness and mobility. Mobility refers to the ability of individuals to move freely and access different places, resources, and opportunities within a society. It is essential for a woman to be able to move freely and confidently to claim her full rights as a human being. However, in the current Afghanistan, even identifying as a ‘woman’ is a crime. For the purpose of restricting women’s rights, mobility is the first right to go. Women are barred from traveling more than 70 kilometers without a mahram or a close male relative. They are mandated to wear a burqa which reveals only their eyes. They are not allowed to work in most sectors other than health and education, and that too with restrictions. Education is limited to primary school only. Secondary schools and universities remain a hopeless dream for most girls. Women are also severely restricted from public spaces in the country as they are not allowed in parks and gyms. Even beauty salons, one of the last women-only spaces, were banned by the Taliban in 2023.

The women-only spaces, salons are also banned:

Women were essentially invisible in public life and imprisoned in their own homes. In Kabul, residents were ordered to cover the Ground floor and 1st floor windows, so that the women inside could not be seen from the streets. If a woman left the house, it should be for a ‘legitimate’ purpose. From infancy, girls and women are under the authority of their fathers or husbands. Their freedom of movement is restricted since they are children and their choice of husbands, education and economic liberty are all denied. With nowhere to go, most married Afghan women are faced with the stark reality that they must endure abuse.

The response of governments and international organizations to this crisis, though, has been poor. But if the world can learn to live with the Taliban’s abuses, with the Afghan women being largely confined to their homes, losing their voice, their personhood, their education, their dreams, and contributions to their communities—then this is a brutal demonstration of how fragile the rights of women and girls are everywhere.

Women are not allowed in public spaces without a “burkha”:

Cambodia

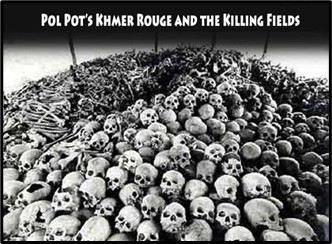

Civil conflict erupted in Cambodia in the late 1960s and lasted 30 years due to the Cold War. The Cambodian revolutionary and politician, Pol Pot and his party, the Khmer Rouge seized power in 1975, committing genocide to enforce agricultural collectives. Post-1979, Vietnam-backed rulers faced resistance. Despite the Paris Peace Accords for disarmament and reconstruction, power struggles persisted, culminating in a coup in 1997.

Skulls of the people who died in the Cambodian genocide:

Cambodian women faced immense socio-economic challenges during the country’s transition to peace. Despite the devastation caused by the Khmer Rouge and international embargo, women, who made up 60% of the population, including many widows and heads of households, played a crucial role. They embraced literacy programs, adopted orphans, and built cooperatives. However, only a few engaged in formal political participation as they were still recovering from economic hardships.

The 1991 Paris Peace Agreement restored political rights to Cambodian women, spurring their involvement in politics and advocacy through NGOs like Khemara. These organizations, dating back to the 1960s, tackled issues like domestic violence and women’s constitutional rights. While women gained access to the 1993 National Assembly and the Ministry of Women’s Affairs, their representation at local levels remained low, with only 10% elected in 1998.

Cambodian women advocating for peace at the grass-root post Cambodian genocide:

This underrepresentation of women highlights deep societal issues, with women facing significant barriers in male-dominated roles due to cultural prejudices and discriminatory policies. Political parties often offer only token support for women’s rights. Despite these challenges, increased female political participation is fostering important discourse on social issues and gender equity in Cambodia. Other examples proving that women actively participated in the wars defying the “victim hood” associated with their conventional roles;

To conclude this article , I would briefly like to talk about the conditions of women in post war zones . If given proper opportunities, women can emerge and have emerged as a driving force for peace. Women play a key role in preserving order and normalcy in the midst of chaos and destruction of the war. Examples abound: Leymah Gbowee’s leadership in Liberia’s peace movement, Nepali women’s advocacy during the civil war, and the efforts of Filipino and Sri Lankan women in local peace initiatives proves the aforementioned statement. In Afghanistan, RAWA continues to advocate for women’s rights amidst ongoing conflict. Post war women contribute more than the government authorities and the international aid in reconciliation and reviving economy and social networking but despite their active role in promoting peace, women tend to fade into the background and are given very little opportunity to emerge as equal stakeholders in the rebuilding of the state . This also makes us understand how quickly patriarchy resurfaces after all the death and destruction, and still manages to marginalize women who are mainly powerless victims and are sidelined in the peace talks. These situations can be utilized as windows of opportunity during which gender relations should be rethought and rewritten. Women should be empowered during and post situations as they deserve a voice and because woman are not just victims, but survivors and fighters of war.

Examples proving how women participating in the post conflict situations is possible and beneficial :

References:

Women and Wars: Contested Histories, Uncertain Futures by Carol Cohn

Women in peacekeeping : A key to Peace, United Nations, https://www.un.org/en/exhibits/page/women-peacekeeping-key-peace

The ComfortWomen : Sexual Violence and Postcolonial memory in Japan and South Korea by C Sarah Soh

Gender, War and History by Laura Sjoberg

What Do Young Afghan Women Do? A glimpse into everyday life after the bans by Jelena Bjelica, AAN team https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/en/reports/rights-freedom/what-do-young-afghan-women-do-a-glimpse-into-everyday-life-after-the-bans/

Mahek Daima

Intern Asia in Global Affairs

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the text belong solely to the author, in his personal capacity. It does not reflect the policies and perspectives of Asia in Global Affairs.