Ecologies of dispossession

Posted on : April 2, 2025Author : Rik Bhattacharya

Ever since the Vizhinjam port project near Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, commenced construction in December 2015, the ongoing ecological debates surrounding its green impact have gained traction over a decade, with both vociferous proponents and determined opponents. The scales are heavily tipped in favour of the former side on account of the Public Private Partnership component, operating on a DBFOT basis, the twin axis of the state and circuits of international finance capital being involved in the making of the seaport. Essentially a Government of Kerala undertaking, the Vizhinjam International Seaport(VIS) is now eyeing for global stature, with ambitions to transform the maritime trade of the state (Kumar, 2025).

VIS is being built primarily as a deep sea transhipment port, its locational niche possibly engendering it a prime positional importance in the international shipping routes connecting Europe, Middle Asia and South-east Asia. Thus, besides being sponsored by finance capital, VIS, once operational, will facilitate and engender a prime position in the global flow of capital. Having established this, the unique case that qualifies VIS as a lone case study is the fundamental contradiction it has been unable to solve- despite severe continuing environmental opposition on account of the ecological destruction its construction and operation will cause, the state and private interests have to project it as being a balancing act of being both ecologically sustainable and essential for the nation’s development and progress.

Initiated by the state, the major part of the project being developed under the auspices of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPIM), which holds office in Kerala since 2016, and financed and executed by private capital, the project is representative of wider patterns of developmental regimes characterised by accumulation by dispossession under neo-liberal auspices (Harvey, 2014: 145-52) wherein the large-scale displacement of people are subsumed under interests of national technocratic development. However, the dispossession also results in praxis of popular resistance by those that bear the brunt of the state-capital nexus (Guha, 2015). This article examines how the mechanisms of capital have dispossessed the local fishing communities in Vizhinjam, and how popular resistance to this developmental regime of displacement have constituted their praxis on the grounds of marine ecology- qualifying it as a study of political ecology, where the non-human component is implicitly foregrounded to make concrete the claims of the anthropocene.

The construction of the port project, locals allege, have wreaked havoc on the coastal economy due to continuous erosion. The environmental danger has also impacted infrastructure and connectivity- running parallel to the Shanghumukham beach, the lone road which connects Kerala’s capital Thiruvananthapuram with its domestic airport has been washed away in places, leading to bureaucratic headache besides extreme transport precarity. The tourist industry has had to be curbed, while religious rituals dependent on access to the beaches have had to be significantly rerouted (Shaji, 2019). For the purposes of the present article, the group most disproportionately affected by such environmental repercussions are the local fishing communities.

The Government of Kerala, which had initially dismissed environmental concerns, is now reluctantly admitting to the degrading ecological effects, but subsuming it under the grander rhetoric of technocratic, and by extension, national interest (Shaji, 2019). Scientific studies show that the project bears several social and environmental costs on marine ecology that have a decisive impact on the lives of the fishers (Joseph & Beegom, 2017). The rich and fragile marine ecosystem of the region bears the brunt of the effects of the marine-side construction and operation of the port- dredging, construction of breakwaters and cargo berths, to name a few. Such activities would naturally impact the seawater quality and the congruent marine ecosystem (Hindu, 2016). The port project is likely to have an adverse impact on the lives and livelihood of the fishers of Vizhinjam as well as of nearby coastal villages due to land acquisition and congruent dispossession, several findings indicate (L&T– Rambøll, 2013; Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishad, 2015).

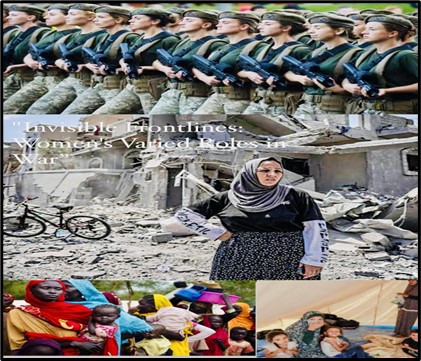

Fishers and citizens during their protest against the port development project at Vizhinjam, in Thiruvananthapuram. 2022. Sourced from: The Hindu

The port project has consequently generated resistance on the part of the dispossessed and threatened local fishing communities. Such resistance of the fisherfolk has been largely led by the Catholic Church, which in itself as a focal point of competing interests, has generated multiple fissures along the axis of class and hence, multiple kinds of discourses surrounding the material benefits the project will accrue, resulting a fractured and often diffused response by the various actors (Ashni & Santosh, 2019: 193-98). The most noted response occurred during August 2022, when the protesting fisherfolk, led by the Latin Archdiocese, Thiruvananthapuram, protested against the under-construction port. The resistance was organised on the grounds of marine ecology, with the fishing communities alleging that the construction of the port has accelerated soil erosion along the beaches, leading to the forced rehabilitation of 300 families due to high-intensity coastal erosion.

The protesters demanded a comprehensive rehabilitation package, an assured minimum wage when the sea turns rough due to inclement weather and subsidised kerosene for boats. On the contrary, the Kerala Government made it clear that since the coastal erosion is due to climate change as reported by various agencies, the demand for stopping the port construction cannot be conceded (Kallungal, 2022). But even such resistance has limits- fear of being labelled as anti-national for holding up the nation’s ‘progress’ has often imposed certain psychological and organisational constraints in the minds of the affected protesting populace (Ashni & Santosh, 2019: 187).

Thus, the Vizhinjam port project, while being representative of neoliberal regimes of accumulation by dispossession, is also an example of twin ecologies- a capital ecology which rests on an ecology of dispossession. It is also remarkable how the state-capital nexus has continued to facilitate the construction of the project, albeit tentatively commercially operational in the first phase since December 2024, and even more ironic when situated in the state’s contemporary structural ideological interventions.

References:

- Ashni, A. L., & Santhosh, R. (2019). Catholic Church, fishers and negotiating development: A study on the Vizhinjam port project. Review of Development and Change, 24(2), 187-204.

- Harvey, D. (2005). The New Imperialism. United Kingdom: OUP Oxford.

- Simon, S. (2021, July 28). Vizhinjam port turning into an eco disaster. Indian Express.

- Kumar, V.S. (2025, February 23). Vizhinjam port vies for global stature. The Hindu

- Guha, S. B. (2015). Accumulation and Dispossession: Contradictions of Growth and Development in Contemporary India in India and the Age of Crisis The Local Politics of Global Economic and Ecological Fragility (pp. 165–179). Routledge .

- Shaji, K. A. (2019, August 20). Is the Deep Water Sea Project in Kerala an environmental and livelihood threat?. Mongabay. https://india.mongabay.com/2019/08/is-the-vizhinjam-port-in-kerala-an-environmental-and-livelihood-threat/

- Kallungal, D (2022, December 5). Why are the fisherfolk demanding to stop the construction of Vizhinjam port project. The Hindu

- Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishad. (2015, December 1). Abandon Vizhinjam Port Project [Press Release].

- Joseph, A., & Beegom, B. (2017). Discourse on development, displacement and livelihood impact on fisherwomen at international deepwater multipurpose seaport. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 22(8), 37–41

- L&T–Rambøll(2013). Comprehensive EIA for Vizhinjam international deepwater multipurpose seaport.

Rik Bhattacharya

Intern, Asia in Global Affairs

The views and opinions expressed in this book review are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Asia in Global Affairs. The review is intended for academic and informational purposes only. It is not an endorsement of any particular viewpoint, nor is it intended to malign any individual, group, organization, company, or government